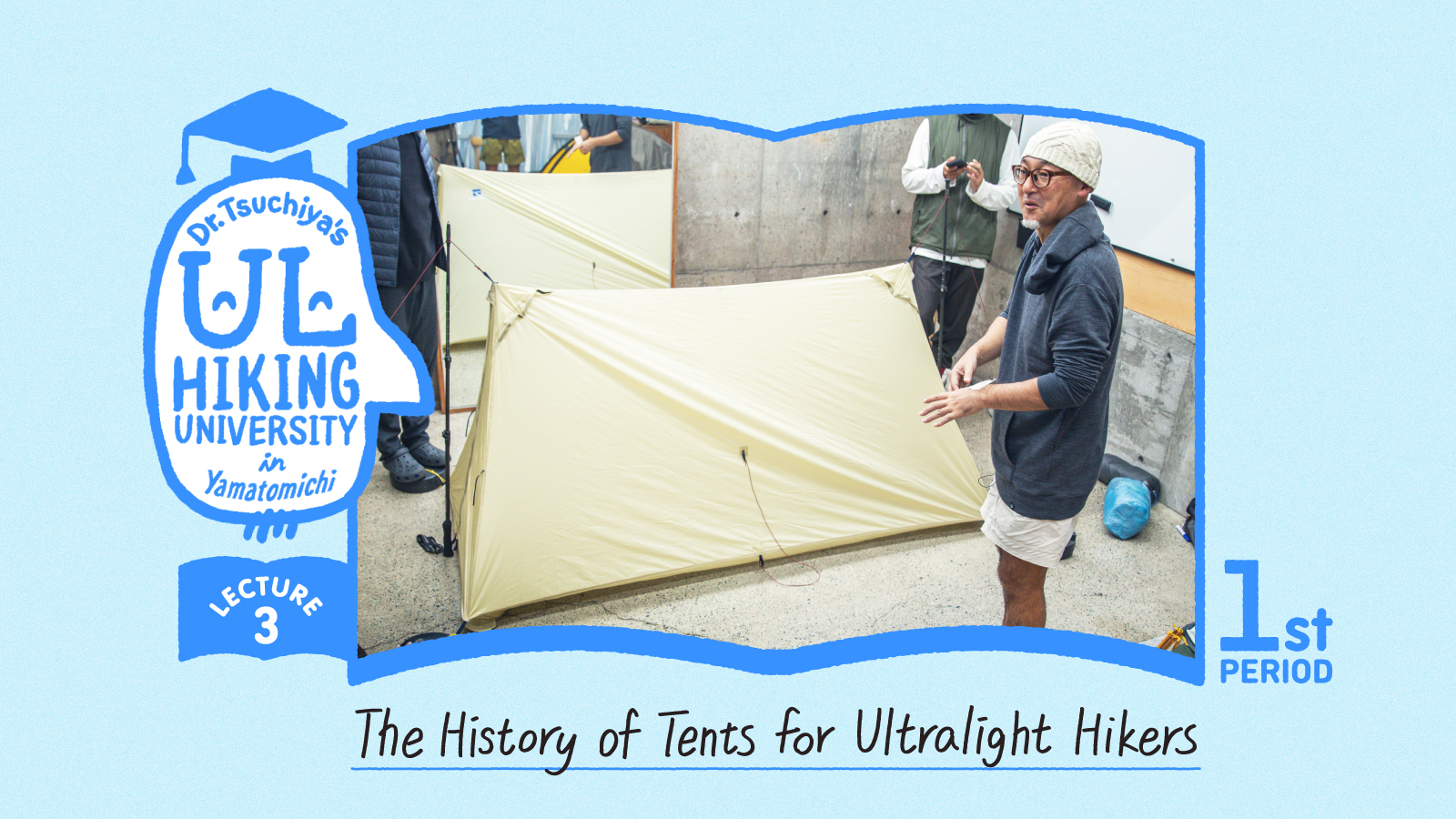

Lecture 3: The History of Tents for Ultralight Hikers

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

Lecture 3: The History of Tents for Ultralight Hikers

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

Tomoya Tsuchiya, owner of Hiker’s Depot in Tokyo and one of Japan’s ultralight hiking pioneers, is the author of Ultralight Hiking (2011) and a frequent Yamatomichi collaborator. Every few months, Tsuchiya hosts a lecture at Yamatomichi’s Laboratory, in Kamakura, covering the history of ultralight hiking and the evolution of its practitioners’ gear, from packs and tents to shoes and sleeping bags. His first lectures explored the birth of ultralight hiking backpacks in the late 1990s and the trends that followed. His second set of lectures delved into the design and structure of footwear, ranging from mountaineering boots to trail running shoes; the mechanics of walking; and techniques for hikers to avoid injury. In this third lecture series, he takes us on a journey into the world of tents. How did tarps evolve into triangular and pyramid tents and, eventually, into the modern dome tent? Why are freestanding dome tents so popular in Japan?

Past Tents

Tomoya Tsuchiya covered the history of backpacks in Lecture 1 and the history of hiking shoes in Lecture 2. For Lecture 3, he leads us on an exploration of tents.

Tomoya Tsuchiya –– owner of Hiker’s Depot in Tokyo, author of Ultralight Hiking (2011), Japanese ultralight hiking pioneer –– speaks with Yamatomichi staff at the Yamatomichi Laboratory In Kamakura, Kanagawa prefecture.

For any hiker, carrying gear in a backpack and having the right footwear are essential. There are different styles of hiking: day hiking, hiking to huts in Japan’s mountains, or staying in huts overseas. However, when it comes to having the freedom to travel –– and sleep –– outdoors, a tent is indispensable.

As I mentioned in Lecture 1 about backpacks, and as Yamatomichi also emphasizes, the core principle of ultralight hiking, base weight (the weight of gear excluding consumables like food, water and fuel), assumes that you’re carrying gear for tent camping. That’s why, in discussing ultralight hiking and the long-distance hiking culture that gave rise to it, tents are such a vital element.

“Tent” is a broad term. There are yurts used by Mongolian nomads, tipis of Native Americans and even small huts in Japan for people who forage for mountain vegetables. Trying to cover all of these would be too unwieldy. So, in this first lecture, I’ll focus primarily on tents used in modern mountaineering, from the first ascents of the European Alps in the 1850s to the history of backpacking in the U.S. from the 1950s onward, while also delving into the history of tents in Japan.

Tsuchiya always speaks without notes or a script –– and, occasionally, without shoes.

Tent history begins with tarps

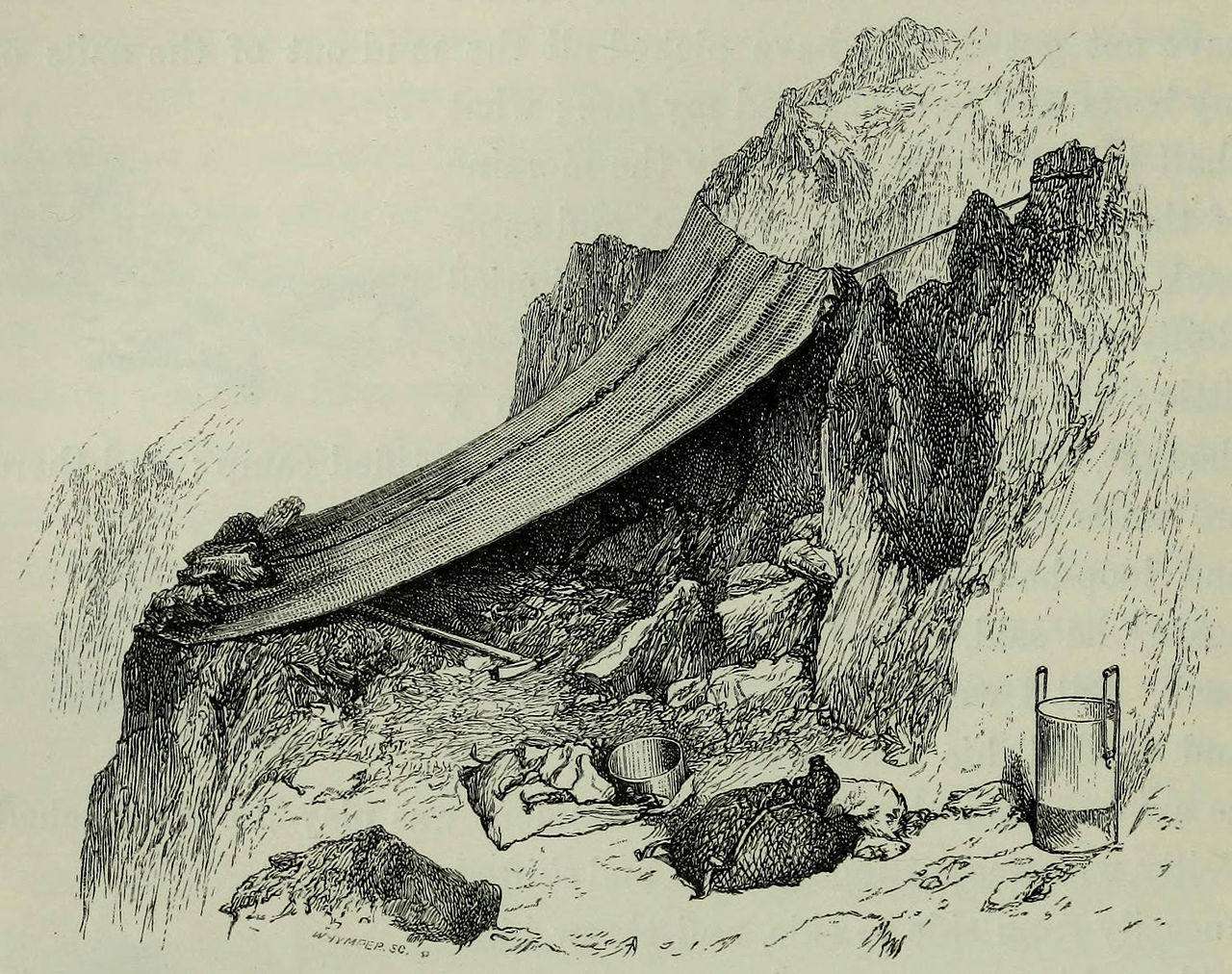

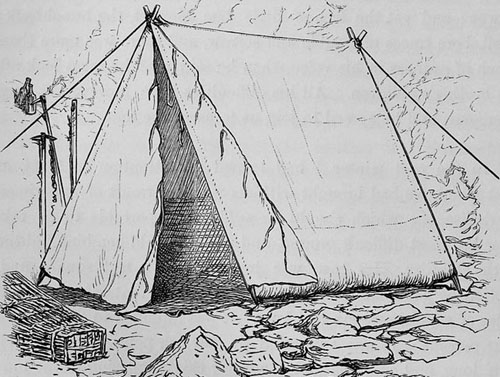

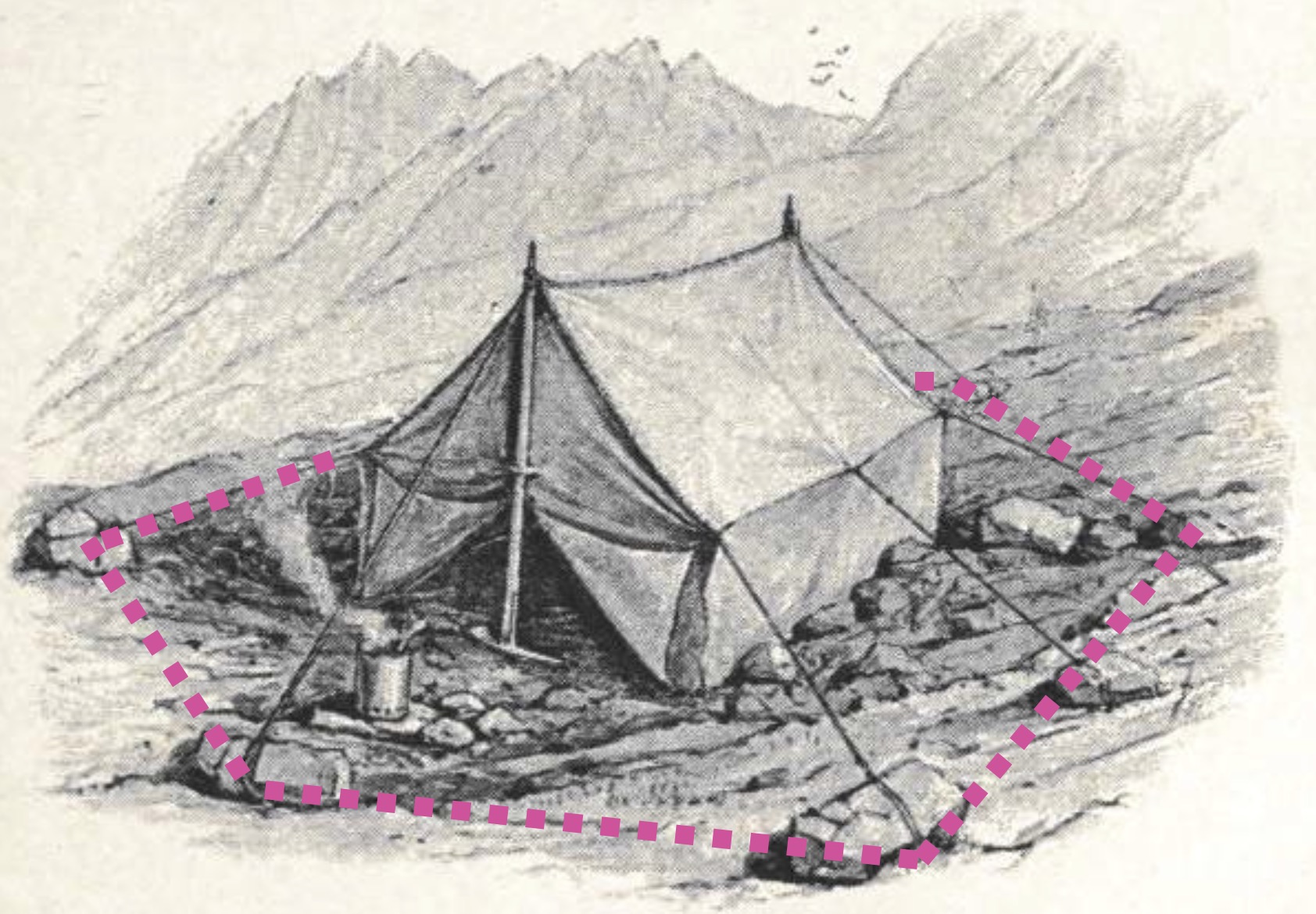

When we think of tents in the mountains, we often picture self-supporting, double-wall mountaineering tents from brands like Arai Tent, Montbell or Heritage. But before the 1850s, lightweight tents didn’t exist. Looking at sketches from that era, we can see that tarps were commonly used even in the European Alps.

This illustration, for example, appears in Scrambles Amongst the Alps (1871), a book by Edward Whymper, who won fame for his first ascent of the Matterhorn, along the border between Italy and Switzerland, in 1865.

From Scrambles Amongst the Alps, by Edward Whymper (1871)(Source:Wikisource)

It’s hard to imagine using a tarp in the mountains in Japan, especially at higher altitudes. But some ultralight hikers here do sleep under tarps in those conditions, and as we can see, tarps were used in the European Alps more than a century ago. Back then, it wasn’t known as a tarp. It was a rectangle of fabric fashioned as a simple roof to shut out rain and wind. In Japan, during the early exploratory ascents of the Northern Alps, guides set up tarps to shield themselves against the nighttime dew. So, as you can see, in the history of modern mountaineering, sleeping under a tarp is the most primitive way of spending the night in the mountains.

Triangle-shaped tents for expeditions in the Alps and Himalayas

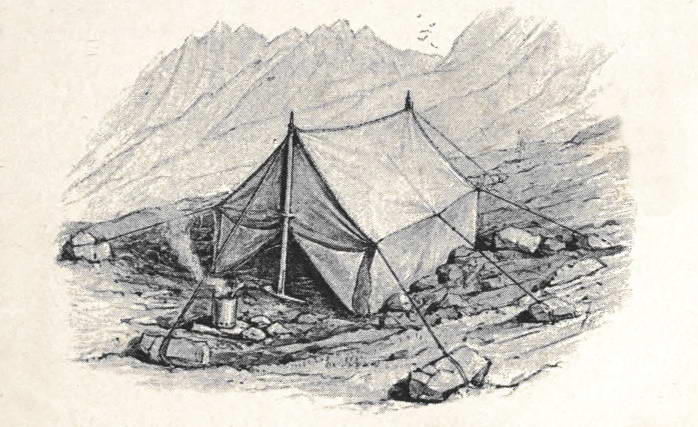

The next type of tent to emerge was modeled on the one that Edward Whymper used during his 1865 ascent of the Matterhorn.

The original Whymper-style tent was made of canvas, had a base of 1.8 m by 1.8 m, and stood 1.7 m tall. It was heavy, weighing around 11 kg. From Scrambles Amongst the Alps, by Edward Whymper.(Source:Wikipedia)

This tent—commonly referred to as a triangle tent—had a square base measuring 1.8 m by 1.8 m and stood 1.7 m tall. Its size was comparable to that of a modern two- or three-person tent, but with a much higher ceiling. The overall shape resembled what many today would recognize as a classic Boy Scouts tent, though its origins actually trace back much further. In fact, the basic prototype of this design dates back to the 1860s. Interestingly, its silhouette also closely mirrors that of today’s ultralight “Zelt” shelters, popular among minimalist hikers.

Tents from that era were primarily made of canvas. Instead of a floor, rubberized mats were placed inside. This stayed the same even when the design evolved later into the house-shaped tents used by the Boy Scouts. Structurally, it closely resembled a modern ultralight floorless shelter combined with a groundsheet.

The poles were made of sturdy wood, and to make them more compact, were sometimes split into two sections with a joint in the middle. This is similar to how modern hikers use carbon or aluminum poles that can be disassembled, which makes carrying and setting up shelters easier. The joint at the intersection of the ceiling had a metal fixture for added stability.

The freestanding dome tent did not appear until the 1970s. For more than a hundred years prior to that, triangular tents were the standard. The next variation that emerged was the Mummery tent.

The Mummery tent. The addition of upright walls improved livability, and the switch to oil-treated waterproof silk reduced weight. Its base measured 1.82 m by 1.21 m, was 1.21 m tall, and weighed 1.6 kg.

(Source:Wikipedia)

Albert Frederick Mummery, an Englishman (1855-1895), was a mountaineering pioneer whose pursuit of “new ascents” and whose delight in “the fun and jollity of the struggle” continues to inspire modern European alpinists.

He was active after the race in Europe for first ascents of 4,000m peaks in the Alps had ended. His focus was on opening more challenging routes, rock climbing and climbing without guides. He was among the first to explore alternatives to established climbing routes –– changing the starting point or attempting different techniques and move sequences to the top –– known as variation route climbing.

Mummery improved upon the Whymper tent by raising its walls to enhance livability. One interesting feature: Instead of carrying dedicated tent poles, he used an ice axe as a support. While modern ice axes have become shorter, around 50 cm, in his time, they were about 1.2 m long and doubled as walking sticks. This is similar to how ultralight hikers today use trekking poles as tent supports. Mummery also replaced the heavy canvas fabric with oil-treated waterproof silk, reducing the tent’s weight from around 10 kg to under 2 kg. Even in the 1870s, tents were already becoming lightweight.

There are two key takeaways here. First, he improved his tent’s weather resistance by increasing the number of anchor points with multiple guy lines –– ropes or cords attaching to the rainfly or tarp and held in the ground with stakes. Second, he created upright walls and expanded the living space by pulling fabric from the guy-out loops. These two principles remain crucial in tent design.

This type of tent was used in the European Alps as well as the Himalayas for more than 100 years. In Japan, around 1936 and 1937, university alpine clubs –– dominant in the Japanese Alpine Club back then –– relied on similar triangular tents resembling tarp shelters for winter climbs here and expeditions overseas. When the Japanese team summited Everest in 1970, their triangular tents with inner poles resembled modern tarp shelters.

You might have had customers who asked: “I should use dome tents because they’re more wind-resistant, right?” For anyone who is new to ultralight hiking and considering non-freestanding shelters, wind resistance is a major concern.

However, tarp-like tents were regularly used in the Himalayas long before self-supporting dome tents emerged in the 1970. So, it’s clear that triangular tents, when properly pitched with enough anchor points, can withstand harsh weather conditions. Whether a tent is freestanding or not, the key factor is securing the guy lines firmly to the ground.

*In his memoir, My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus (1895), Mummery wrote: “The true mountaineer is a wanderer, and by a wanderer I do not mean a man who expends his whole time in travelling to and fro in the mountains on the exact tracks of his predecessors—much as a bicyclist rushes along the turnpike roads of England—but I mean a man who loves to be where no human being has been before, who delights in gripping rocks that have previously never felt the touch of human fingers, or in hewing his way up ice-filled gullies whose grim shadows have been sacred to the mists and avalanches since ‘Earth rose out of chaos.’ In other words, the true mountaineer is the man who attempts new ascents. Equally, whether he succeeds or fails, he delights in the fun and jollity of the struggle. The gaunt, bare slabs, the square, precipitous steps in the ridge, and the black, bulging ice of the gully, are the very breath of life to his being. I do not pretend to be able to analyse this feeling, still less to be able to make it clear to unbelievers. It must be felt to be understood, but it is potent to happiness and sends the blood tingling through the veins, destroying every trace of cynicism and striking at the very roots of pessimistic philosophy.”

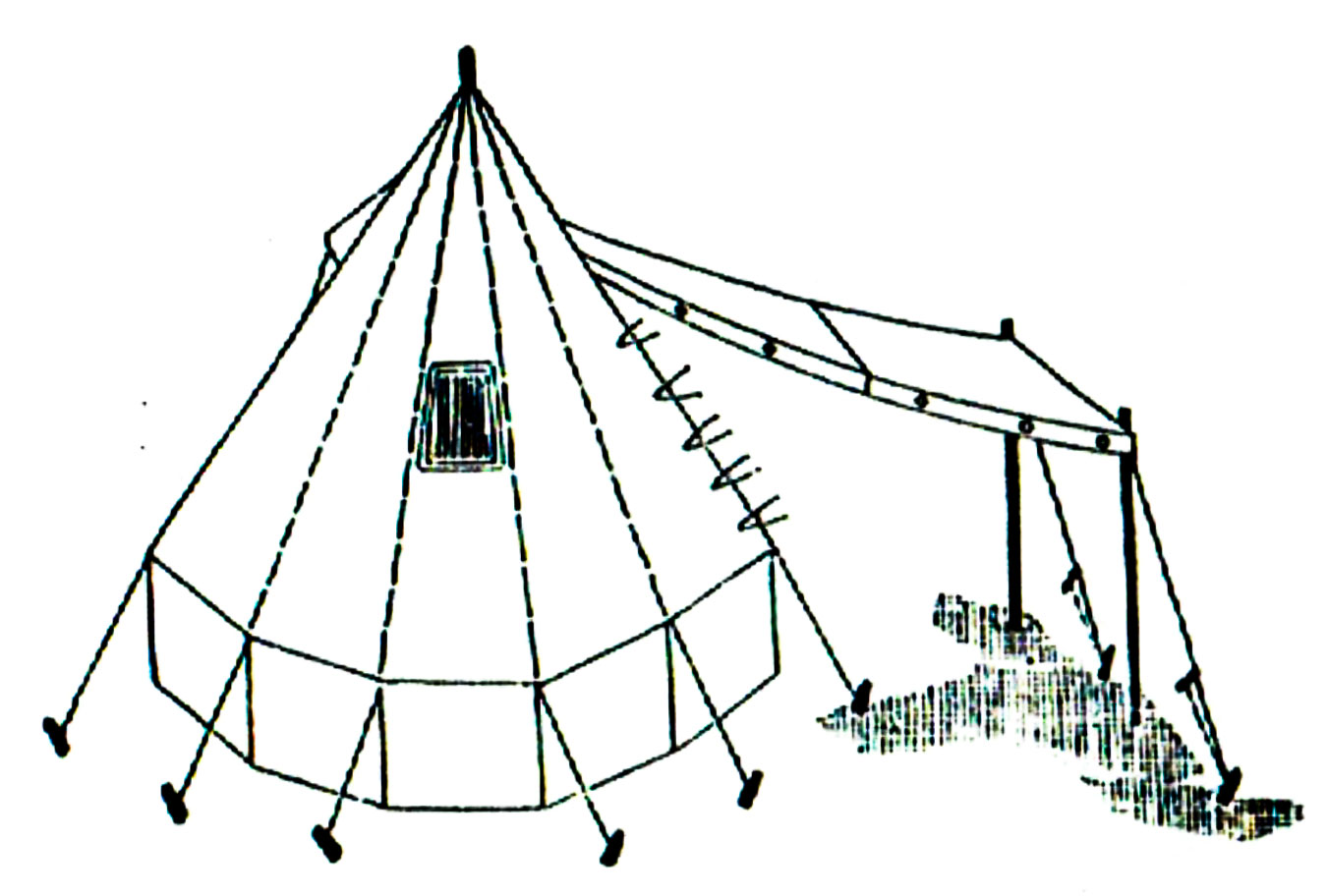

Japan’s first mountaineering tent was pyramid-shaped

Modern mountaineering is rooted in European alpinism. That’s also true in Japan. The first type of mountaineering tent developed in Japan had a pyramid shape, which is similar to what we now call a one-pole tent or pyramid shelter.

In 1909, mountaineering brand Katagiri, known for the Kisling backpack, designed a pyramid-shaped tent for mountaineering. It was created for Kojima Usui’s* traverse of Japan’s Southern Alps, when exploratory mountaineering was in its infancy here. So, the pyramid-shaped shelters we often see today actually have a long history.

*Usui, a trailblazer of modern mountaineering in Japan, was the first president of the Japanese Alpine Club and an essayist who wrote numerous travelogues.

The tent used by Kojima Usui, during his traverse of the Southern Alps in 1909, was made of canvas and had bamboo poles. It weighed around 7 kg. (Source: Japanese Alpine Club magazine, Sangaku, Vol. 8, No. 2)

These pyramid-shaped or conical tents with pointed roofs were used even in polar and high-altitude regions because, when pitched properly, they are effective at deflecting wind.

For anyone who is only familiar with freestanding dome tents, pyramid shelters might seem unconventional or even a recent, trendy development. In reality, they have been around since the earliest days of tent use.

From the 1850s to the early 1900s, tents evolved rapidly: from simple tarp-like setups to the early versions of A-frame tents, to pyramid and conical designs of increasing variations.

Zelt: lightweight tent pioneer

That historical perspective was something I revisited when, in 2011, I collaborated with Finetrack (founded by Yotaro Kanayama, in Kobe, in 2004) to develop the Zelt II Long at Hiker’s Depot. Redesigning the zelt (pronounced “tselt”, from the German word for tent) was like rediscovering some ancestral wisdom and applying it to the modern era.

In ultralight hiking, the goal of reducing your packweight involves an act of simplification –– getting rid of nonessentials. By looking at past innovations, we can find solutions that remain relevant even today.

The Zelt II Long, developed by Hiker’s Depot in collaboration with Finetrack, became a bestseller when it was first released, and is now a fixture in Finetrack’s product lineup. It sits alongside the sacoche as an iconic product that represents the ultralight movement in Japan. (Source: Hiker’s Depot)

Let’s talk about the zelt.

The zelt’s lineage can be traced back to the classic triangular-roof shape of the Whymper and Mummery tents. In the past, those tents lacked a floor, so campers carried a separate rubberized mat. Even traditional Boy Scout and summer camp A-frame tents had separate fabric floors, which were tied to the tent walls with cords.

The zelt we’re familiar with today evolved by extending fabric from the walls and tying it together in the center to form the floor. But it wasn’t until the early 1970s that this design was refined by Arai Tent and sold at Ishii Sports stores.

The Zelt II Long features fabric that extends from the slanted tent walls (Source: Hiker’s Depot)

The prototype of the modern zelt (with an integrated floor) weighed 950g and was made from 70-denier nylon taffeta. A half century of innovation led to materials that were progressively thinner and lighter.

In the 1970s, solo tents were a rarity. Most tents used for mountaineering were designed for sharing: 2 or 3 people, 4 or 5, or even 8. The zelt was primarily seen as an emergency shelter. Some climbers used zelts for solo ascents, but there were limits to what was possible alone on first ascents or when scaling higher, more difficult peaks. The standard approach was to form a climbing party.

As climbers in Japan began attempting increasingly difficult routes, they often went in smaller teams or pairs. For these trips, conventional tents were too heavy. Many climbers opted for the comparatively lighter Arai Tent Zelt, which weighed 950 g and was 182 cm long, 130 cm wide and 110 cm tall. That was shorter in length (with a lower ceiling) than modern versions of the zelt. According to Arai Tent, the Zelt’s length was initially limited by the machines used for weaving: 94 cm was the standard fabric length. Back then, two fabric panels were the standard length for the Zelt and other tents. (In the late 1980s, new weaving machines allowed Arai Tent to increase tent length to 200 cm.) Since many of the climbers who were using Arai Tent’s Zelt were rock climbers, the shorter length was more practical for pitching the tent on narrow rock ledges where space was limited.

Dome tents' groundbreaking curved frame

In the 1970s, around the time that zelts were winning fans, tent design had its breakthrough moment: The freestanding dome tent was born. It featured poles that were curved, instead of relying on straight, rigid wooden supports (or ice axes).

American designer Bill Moss invented the first tent with a dome shape –– called the Pop Tent –– in 1955. Its fiberglass poles were flexible and had a natural tendency to snap back to their original shape, which stretched the tent fabric taut. The Pop Tent earned praise as “the most beautiful tent in the world”. No surprise that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York acquired one for its collection.

In 1955, American designer Bill Moss introduced the Pop Tent, the world’s first dome-shaped camping tent. (Source:Bill Moss: Fabric Artist & Designer, by Marilyn Moss)

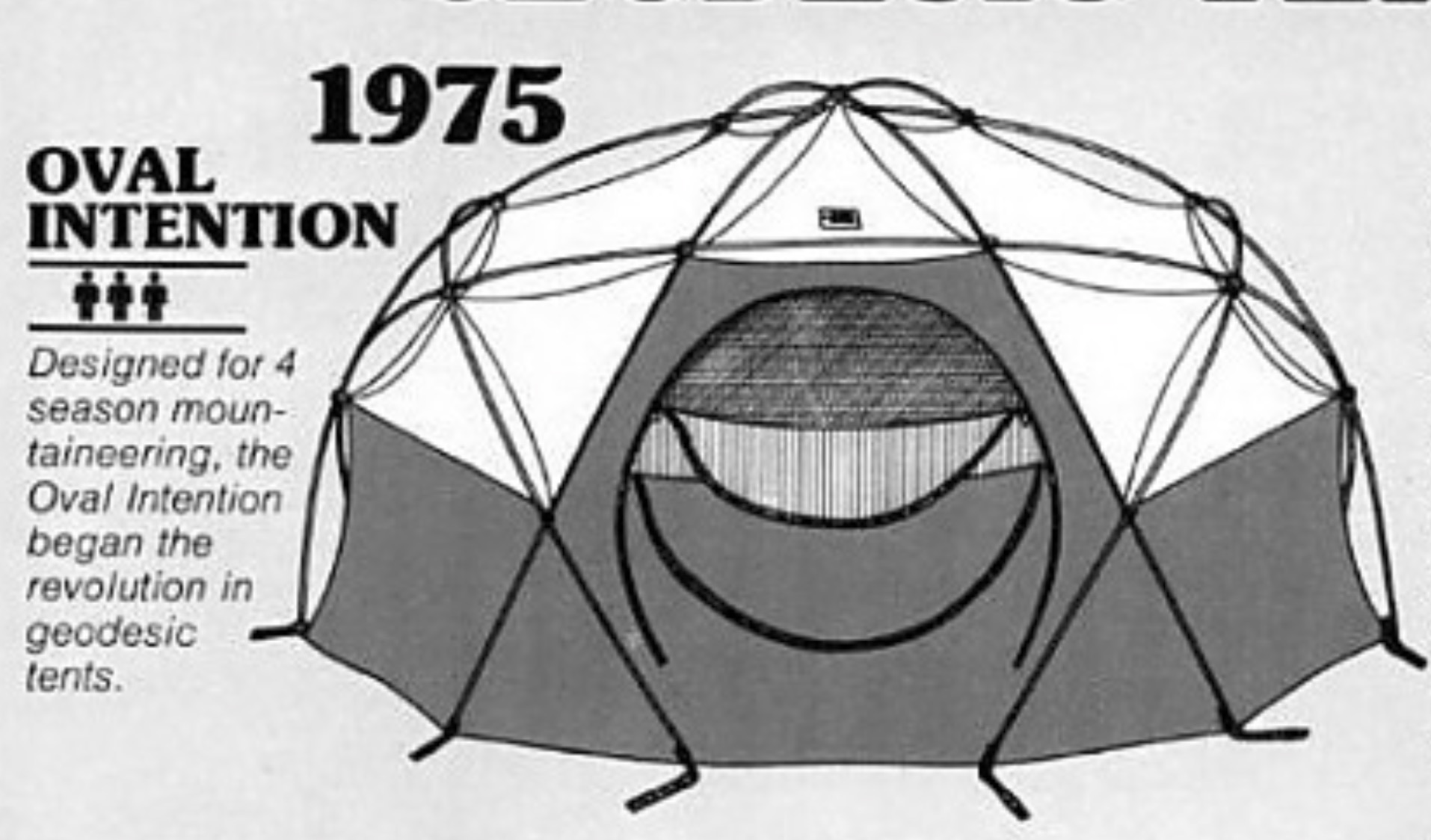

In 1975, The North Face in the U.S. released the Oval Intention tent, which was shaped like a geodesic dome and resembled the weather radar at the summit of Mt. Fuji. Nowadays, when people think of dome tents, they picture its having two flexible poles for support. But early versions of freestanding dome tents from North American manufacturers relied on a web of poles. Back then, the design was more about proposing a new kind of architecture and less about cutting down on weight.

The North Face’s geodesic dome-shaped tent was released in 1975. (Excerpt from a poster created by The North Face in 1979)

In 1970, the release of Japanese brand Espace’s sleeve-style freestanding dome tent, followed a year later by Dunlop’s suspension-style freestanding dome tent, led to the spread of this innovative design in Japan.

Japan’s first freestanding dome tent, by Espace, was introduced in 1970.(Source:ヘリテイジ)

Advantages of dome tents

Freestanding dome tents are now the standard for mountaineering in Japan. They are often lauded for their resistance to wind and rain. But that’s not their biggest advantage. Other designs, such as tunnel tents or pyramid tents, are also used in extreme conditions. So, what’s unique about freestanding dome tents?

One advantage is that it’s easier to visualize setting one up, compared to tents that require anchoring to the ground. I don’t necessarily agree that freestanding dome tents are quicker or easier to pitch. Some experienced hikers might argue that zelts and non-freestanding tents are also simple to put up, once you get used to them. But the fact that the tent takes shape when you insert the poles makes the setup process easy for anyone to grasp. It’s the perception that counts: dome tents seem easier to set up, which lowers the psychological barrier to using a tent.

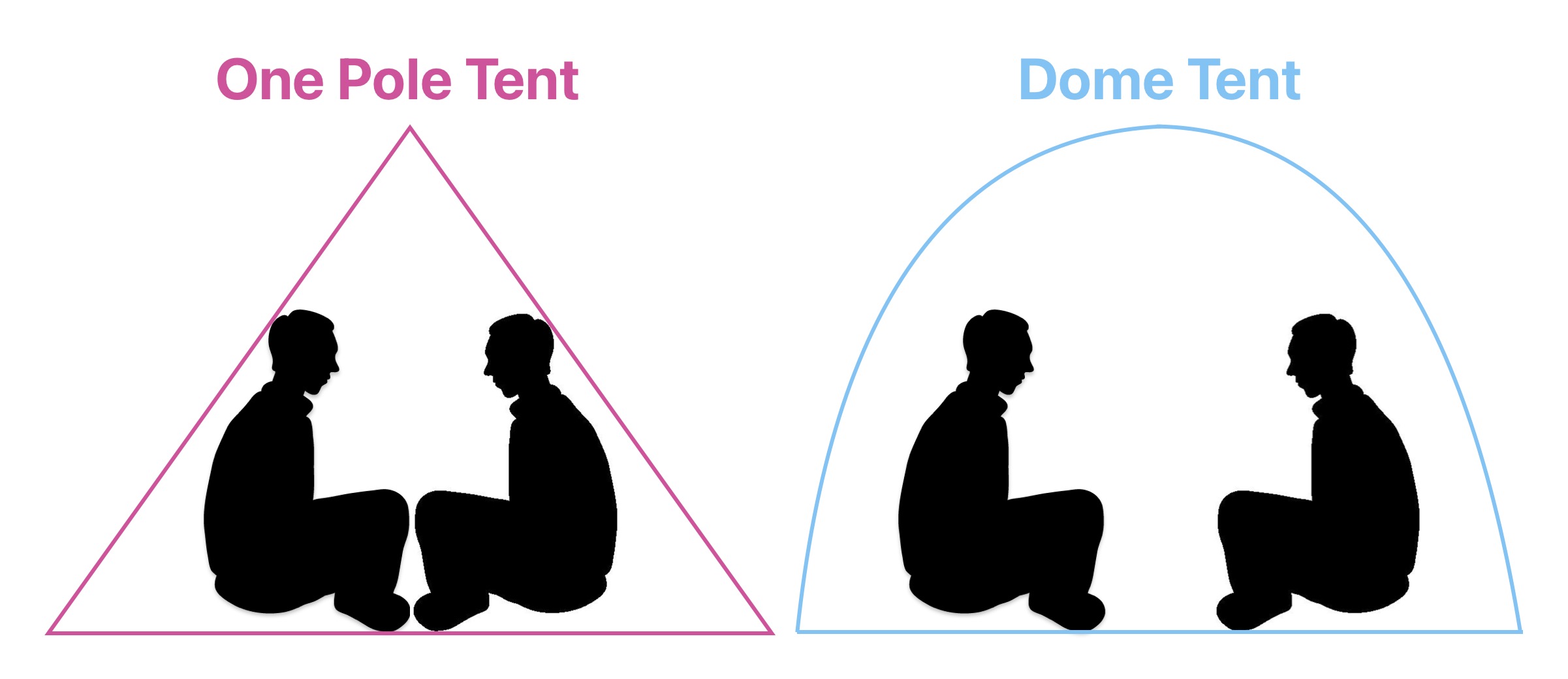

Another advantage to using a freestanding dome tent is their practical functionality. A dome is roomier inside. Traditional linear tent structures have slanted walls. Anyone who has used a single-pole tent knows that, while there’s enough room to sleep, you’re often hitting your head when sitting up. The walls can feel like they are closing in on you. This is, ultimately, the dome’s biggest advantage: with more living space inside, it’s easier to accommodate a group on a mountaineering trip.

With the same floor area and ceiling height, a dome tent with curved walls and ceiling is significantly more livable than a single-pole tent with straight walls.

The third advantage: dome tents take up less space. Creating the same amount of interior space with a triangular tent requires a much bigger floor area. Many hikers who carry single-pole shelters have likely wondered when reaching a campsite, “Will there be enough space to pitch my tent?”

Of course, for maximum wind resistance, even dome tents need guy lines anchored to the ground. With dome tents, the poles determine the fundamental shape. On the other hand, a Mummery tent needs guy lines to retain its shape, so it takes up an area that extends beyond its floor.

Designs like the Mummery tent require significantly more space for guy lines than the floor area inside.

Dome tents are not automatically wind-resistant

Dome tents are an overwhelmingly popular choice in Japan because they’re spacious inside without taking up ground space. That makes sense in Japan, where much of the land is mountains and steep terrain. In the Northern Alps, tent sites often have limited space, and finding flat ground when camping outside of these designated sites can be a challenge. Dome tents solve this problem.

In Europe, tunnel-shaped tents made by Swedish manufacturer Hilleberg and others are more common. This design is wind-resistant and is frequently used on polar expeditions. In Northern Europe, where space isn’t a limiting factor, dome tents are less of a necessity.

Tent design is heavily influenced by geography. Just remember: Focusing only on the wind-resistance of dome tents oversimplifies things. It might even suggest that other designs are inferior. But Whymper tents and pyramid tents have also been used in extreme conditions. The fact is, all tents offer a practical level of wind-resistance when properly set up. That’s the key lesson here: When you’re discussing tent features with customers, wind-resistance is only one of many factors that they should take into consideration.

[To be continued in the Second Period]