YOSHIAKI NISHIMURA “Listening” #2

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

YOSHIAKI NISHIMURA “Listening” #2

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

In the HIKING AS LIBERAL ARTS series, hosted by Yamatomichi HLC (Hike Life Community) director Hideki Toyoshima, we consider hiking as a liberal art, a field of study that liberates individuals from preconceived notions and norms, empowering them to act based on personal values. This series delves into the physical aspects of hiking ー seeing, hearing, eating ー for clues to exploring the value of and potential that extends beyond hiking.

This is Part 2 with our second guest of the series, Yoshiaki Nishimura, a planning director, researcher and author who delves into the different ways that we work. After discussing the essence of listening intently to the sounds that surround us, we take time delving into what it means to listen to people’s stories ー the focus of Yoshiaki’s work.

Restoring humanity and backpacking

ーIn the first part, we discussed the act of listening in the sense of paying attention to the sounds of nature. In this second part, I would like to ask about listening in the sense of taking in people’s stories. Would you say that clinical psychologist Carl Rogers has had a significant influence on your thoughts regarding listening to people?

In the 1960s, Carl Rogers introduced the three core qualities of active listening. While working at a child guidance clinic, he recorded around 2,000 counseling conversations between parents and children on open-reel tape and produced verbatim transcriptions. Through this process, he realized that the person struggling with concerns or problems would repeatedly discover their own path forward simply by speaking, if the listener possessed three specific qualities: empathy, unconditional acceptance and congruence. That is, an empathetic understanding of the other person, a sense of unconditional acceptance and a consistency between the listener’s feelings and actions. Rogers noticed that when a person speaks to a listener who embodies these qualities, it triggers an involuntary, intrinsic growth process for the speaker.

Although Rogers initially regarded these qualities as a hypothesis, they gained significant influence, and many people began treating them as fundamental principles. In counselor training settings, the emphasis was often placed on teaching these core qualities as doctrines before allowing trainees to fully experience empathy themselves. The result was that a peculiar form of listening emerged: people mechanically expressed empathy and affirmation without truly listening to what was being said.

ーRogers was active in 1960s America, if I’m not mistaken. The 1960s was also when backpacking and extended trips into the mountains started gaining in popularity. There were surfers, climbers and even hippies returning to nature. Many were also exploring new concepts of body and mind. I feel that these movements have resurfaced in the 2020s, along with contemporary trends of restoring humanity and returning to nature.

The human potential movement of the 1960s was closely associated with hippies, and took place against the backdrop of the Vietnam War. It manifested in two major ways. One was the “Be-In” (*1) movement, in which people gathered in large numbers to reaffirm their perspectives on life and society. The “Be-In” was about empowering each other through gatherings.

Around the same time, another movement emerged: people embarking on extended solo journeys, carrying only what they needed to survive alone in the mountains. While one trend encouraged large gatherings and social connections, the other focused on venturing into the wilderness alone, connecting with nature, and reconnecting with oneself by walking. I find the latter to be very relevant now.

ーThat’s exactly what backpackers and hikers continue to do today.

(*1) The “Be-In” (Human Be-In) was a countercultural event that began in San Francisco in 1967, bringing together individuals seeking to restore humanity in society. This event became a catalyst for the expansion of the hippie movement, philosophy and ideology across the U.S.

The interview took place at Levain Tomigaya, a bakery in Tokyo that Yoshiaki frequently visits.

Listening workshop

ーPreviously, you mentioned that among your various activities, the interview workshop felt particularly right for you. Could you tell us more about the interview workshop you lead?

What I do in the workshop is essentially a process of re-examining two key questions. What does it mean to listen to someone? What is a person actually doing when they speak? The participants are usually people who want to reassess their way of listening. At first, they tend to compare their listening style with the way I demonstrate, which makes them overly conscious of whether they are listening well or not. But in that moment, they’re not really listening at all, because instead of focusing on the other person, they’re allocating their cognitive processing power to themselves.

When you really listen, the other person is allowed to speak. The workshop is about resolving the difference between moments when people feel they are able to talk and when they feel they can’t. Many people believe that properly listening means intellectually and accurately understanding the content of what is being said. But that’s like reading the lyrics of a song without hearing the melody. In reality, even now as I speak, I’m not just talking. I’m singing: There’s intonation, rhythm, dynamics and even physical movement involved.

ーThat’s true. When we speak, we’re not just conveying words. There’s a lot more being expressed.

Yes, it’s about the way someone speaks; their manner of speaking. In fact, that expresses even more than the words themselves. It’s deeply physical. The body moves much faster than we consciously think. Cognitive science has shown that human beings don’t move their bodies because their brain first decides to do so. Rather, the body starts moving first, and the brain follows, attaching meaning afterward.

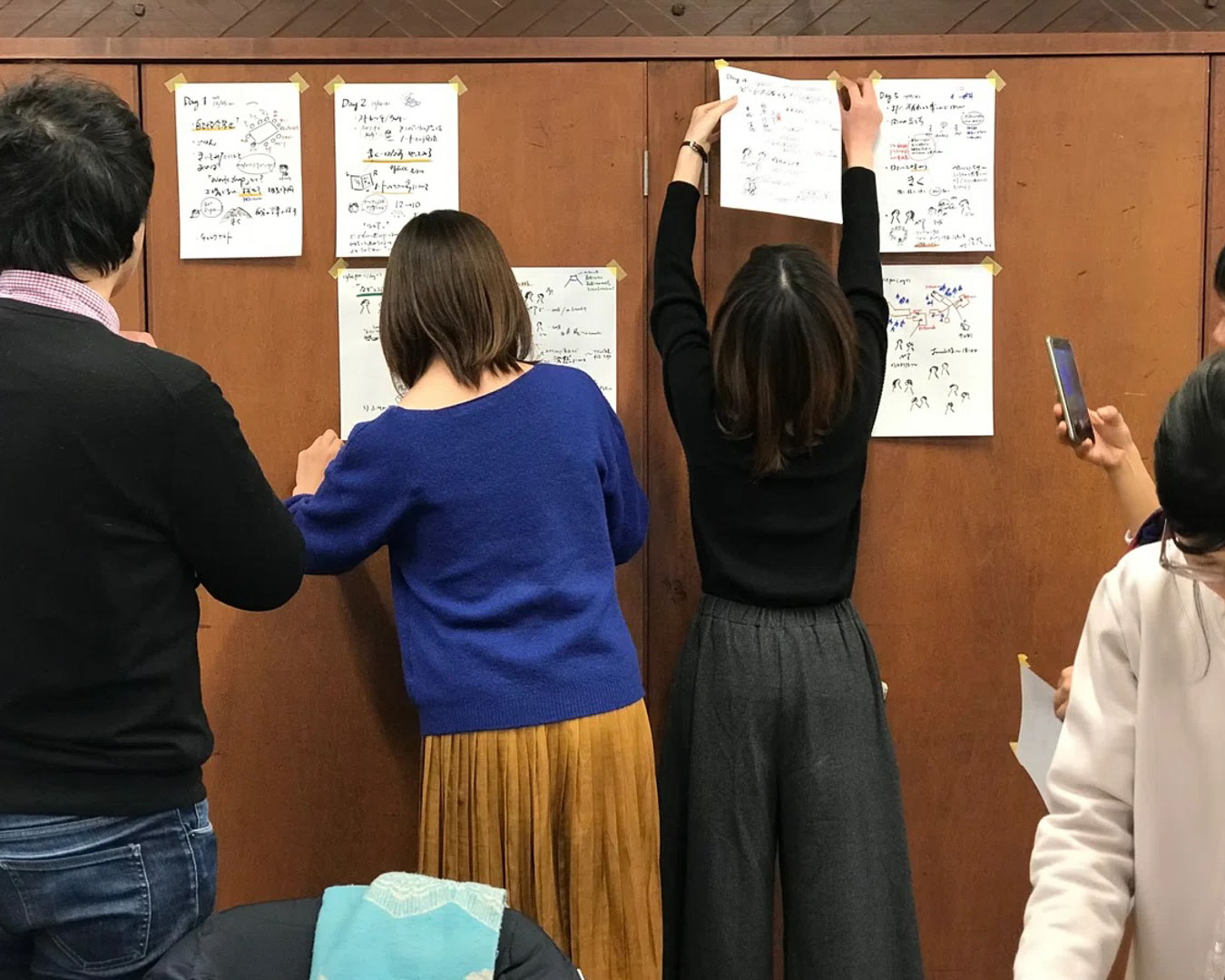

When we become attuned to what the body is expressing, the nature of the conversation itself changes. The workshop is designed to help participants develop over several days the ability to receive and sense that.

Scenes from one of Yoshiaki’s interview workshops. (Photo credit: Yoshiaki Nishimura)

What is a "non-structured encounter group"?

ーOne of the other workshops you conduct is what’s known as a “non-structured encounter group”. Can you explain what that is?

The non-structured encounter group is a type of group session started by Carl Rogers. The only thing set in advance is the mealtime. Participants gather in a circle, and whoever feels like speaking does so. That’s it.

Allow me to share my first experience, to give you a sense of what it’s like. I wanted to participate as a member, so I asked someone else to facilitate. Thirteen people from different regions came together, all meeting for the first time. The facilitator said: “We will now begin the non-structured encounter group.” Then, there was silence. About three minutes later, someone asked: “Is this starting?” But the facilitator didn’t respond. The silence itself signaled that the session had begun.

Every few minutes, someone spoke, but the conversations didn’t last long. The session went on for four days and three nights. There was no set agenda, no guiding questions, and the facilitator didn’t lead or organize the discussion. We simply responded to whatever came up at any particular moment. And yet, there was a natural sense of fulfillment. Even without predetermined themes, questions or activities, things happened as they were meant to, and the members grew from the experience. It might not make much sense just hearing about it, but witnessing how the session sustains itself without falling apart or losing momentum was shocking for me.

ーIs talking a requirement in the non-structured encounter group?

Not at all. I’ve participated in these groups about 15 or 16 times, and there was one instance when we remained in complete silence for nearly two and a half days. I learned that even if I don’t rush to introduce a new topic, whatever needs to happen will unfold naturally. Because of this trust in the process, I’ve become more comfortable with waiting in silence, whether in meetings or when listening to someone speak.

ーWhat do participants gain from the non-structured encounter group?

It varies for each person. For me, it completely changed how I see people. Before, when joining a workshop, I quickly divvied up the group into people whom I might get along with and people with whom I’d probably have zero chemistry. But after spending days together with the others, I often found my initial impressions to be entirely wrong. It made me question what I had been perceiving all along.

For a while, after I started participating in non-structured encounter groups, I stopped traveling abroad. I felt that I no longer needed to go far away. What I had right in front of me was enough. It wasn’t just about listening to conversations; it was a completely different kind of experience.

ーThat sounds like a fascinating and unusual experience. It’s not something that happens often in daily life, is it?

Actually, moments like that do exist in everyday life. For example, when listening to someone talk, there are times when you instinctively respond with something like, “That sounds painful.” Or, you might say, “Wow, that’s unbelievable!” When those words come out, you’re already halfway inside the other person’s story, feeling what they felt. That’s what empathy is. The sensation that arises between two people in that moment is very similar to what happens in a non-structured encounter group.

ーThat’s not something we usually pay attention to in daily life. In a previous conversation, Roger McDonald, who advocates for “Deep Looking”, also emphasized the importance of patiently observing.

People today have very little tolerance for silence. For example, on TV or radio, silence lasting longer than four seconds is considered a broadcasting accident. In everyday life, people try to avoid any gaps or pauses, even when simply drinking tea. Everything moves at a fast pace, with no space in between.

But if you look back, many cultures had a natural acceptance of silence. For instance, there’s a scene in Japanese folklore scholar Tsuneichi Miyamoto’s book, The Forgotten Japanese (*2), describing village gatherings at which long periods of silence were common. Perhaps the most essential things emerge from silence.

(*2) The Forgotten Japanese: Encounters with Rural Life and Folklore, by Tsuneichi Miyamoto (1907–1981), documents the stories of elderly people who built and sustained local cultures. Miyamoto traveled extensively across Japan, meticulously collecting oral histories of various folk traditions.

The scene during a break in a non-structured encounter group session. (Photo credit: Yoshiaki Nishimura)

ーI’ve taken a 10-day Vipassana meditation (*3) course, during which you don’t make eye contact or have conversations with anyone. But even without speaking, you start to sense whom you might connect with, just by being in the same room meditating together. On the last day, when you’re finally allowed to speak, you realize that you truly do connect with certain people.

I think it’s the same. Earlier, we were talking about silence, but from a different perspective, we live in a society where articulate people dominate. The ones who express themselves with strong words hold the power. Authority stems from this emphasis on “meaning”. But I focus more on “feeling”; the “feeling” of something being right. That’s what I try to be conscious of in my work and when I’m listening to someone.

ーSo it’s not about listening with just your ears.

It’s about the way people speak, their tone, their endings. In Japanese, you can express your feelings or make decisions about your attitude toward something as you’re speaking. The ending of the sentence contains information about your feelings. For example: ending with “da” (it is), “kamo” (maybe) or “mitaina” (something like). Essentially, Japanese is a language that allows people to speak freely while processing and reflecting on what they feel or think. When you catch that and respond accordingly, you’re continuously responding to the person in that moment. This changes the quality of the relationship and the conversation itself. I practice this in interview workshops, and when I facilitate the non-structured encounter group, I’m conscious of this, too.

ーIt sounds like a “non-structured hiking group” could also work. Just walking with strangers without saying anything.

I think hiking is already that kind of experience.

(*3)Vipassana (“seeing things as they truly are”, in Pāli, a liturgical language that’s studied to understand ancient Buddhist scriptures) is thought to be one of the oldest meditation techniques in India. Practitioners view the technique of observing the self in the “present moment’s reality” as a means of achieving peace of mind and leading a happy, useful life.

Hideki (L) and Yoshiaki (R) respond to the “present moment’s reality” as they chat. The two have been friends for more than two decades.

Is the non-structured encounter group similar to hiking?

ーI don’t mean to force a comparison with hiking, but I can’t help but thinking that they are quite similar. Over the course of our conversation, I started thinking about why we go hiking, and I realized that it has the same underlying essence as a non-structured encounter group session. Unlike mountaineering, which has a clear goal of reaching the summit, hiking is more about wandering or immersing yourself in nature. Walking is the point, which is what makes it so interesting. I think that the same thing can be said about a non-structured encounter group.

The Japanese word 逍遥 (shōyō) means “to stroll about freely, to enjoy oneself away from worldly concerns, to wander without a fixed destination”. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Earthsea Series (*4), there is an elder who teaches the protagonist, Ged, about the way of the wizard. This elder spends his time constantly wandering through the forest, without any particular goal. He simply walks. I think hiking is quite close to this kind of wandering.

ーClimbing mountains like the Yatsugatake range, the Northern Alps or even mountains overseas often feels like a special event in daily life. If we tie this to the Japanese concepts of “hare” and “ke” (hare refers to the extraordinary or non-everyday, ke to the ordinary or everyday), mountaineering falls into the “hare” category as a special occasion, like a festival or ritual, that’s separate from the everyday. On the other hand, a casual hike up the hill behind your house, which you can do on a whim, would be in the “ke” category because it’s part of everyday life. There are moments during these ordinary hikes that can be deeply moving. This is something that only someone who goes on these hikes daily would understand. But because such everyday activities become routine, they’re harder to appreciate. To truly recognize and indulge in the joy of everyday life, you need a certain level of focus, presence, commitment to the moment, respect for the time and the awareness that life is not just about efficiency or speed. Without these, you might not recognize the richness of these seemingly mundane experiences. I believe that this also applies to hiking.

Hearing you talk about it makes me think that non-structured encounter groups and hiking overlap in many ways. For example, in writing workshops, people are often taught to prepare 100 questions before conducting an interview. While it’s not necessarily bad to come up with specific questions in advance, I personally think it’s counterproductive to stick to a script. When you have prepared questions, there’s pressure to use them, and instead of really engaging with the person you’re interviewing, you focus on checking off questions on your list. As a result, the interview becomes a dry question-answer exchange. It’s always better to adapt to what’s happening in the moment. This reminds me of the ultralight hiking philosophy of carrying less. Today’s conversation has made me see the deep connection between hiking and non-structured encounter groups.

(*4)The Earthsea Series is a fantasy novel series written by American writer and sci-fi author Ursula K. Le Guin (1929–2018) and published between 1968 and 2001.

Reflections on Yoshiaki’s story

HIDEKI TOYOSHIMA

I have known Yoshinori Nishimura for more than two decades. Over the years, we have had many conversations at events and workshops and for interviews and other projects. I occasionally take part in public discussions or sit for interviews. But whenever my conversation partner is Yoshiaki, it always feels different. I end up talking more than usual. Sometimes, I have moments of heightened self-awareness: I even catch myself divulging things I hadn’t consciously realized about myself. It’s as if Yoshiaki has guided me to discover parts of myself I hadn’t known before.

I tend to over-explain things. This is probably because I want people to fully understand my thoughts. No one knows this better, or suffers from it more, than my wife. It’s not so much about arguments or debates. I just tend to go on and on, explaining and re-explaining, until I realize what I’m doing. Which is partly why listening to Yoshiaki talk about listening resonates with me on such a deeply personal level.

It’s also a broadly relevant and universal topic. Yoshiaki’s Sound Bum project taught hikers a new way to perceive the world. His points about the connection between Carl Rogers’ humanistic movement and backpacking would excite any hiker.

You’ll recall Yoshiaki’s explanation of two countercultural trends in the late 1960s in the U.S. Some people were participating in large gatherings to reaffirm their perspectives on life and society. Others were embarking on extended solo journeys into the wilderness, carrying only what they needed to survive, connecting with nature and reconnecting with themselves. This echoes what we practice at Yamatomichi HLC.

In the first part of our conversation, Yoshiaki explained how trying to listen to the sounds of the natural world can change your sense of scale. I want to do this, expanding my own perspective, taking in my surroundings through vibrations felt within my body. I also want to participate in a non-structured encounter group, which remains a bit of a mystery to me. By focusing more on the act of listening, I hope to upgrade my sensitivity as a hiker and enjoy the experience even more. Thank you, Yoshiaki!