YOSHIAKI NISHIMURA “Listening” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

YOSHIAKI NISHIMURA “Listening” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

Hiking is an effective way for us to physically engage with, understand and maintain — restore, even — our connection to nature and the world. This is particularly true with ultralight hiking, which by minimizing gear and allowing for longer, more comfortable walks, heightens the sense of being in communion with nature.

In the HIKING AS LIBERAL ARTS series, hosted by Yamatomichi HLC (Hike Life Community) director Hideki Toyoshima, we consider hiking as a liberal art, a field of study that liberates individuals from preconceived notions and norms, empowering them to act based on personal values. This series delves into the physical aspects of hiking ー seeing, hearing, eating ー for clues to exploring the value of and potential that extends beyond hiking.

Our second guest is Yoshiaki Nishimura, a planning director and researcher who delves into the different ways that we work. The author of books on work and employment, Yoshiaki has contributed to the revitalization of Japan’s farflung regions, advised businesses on shifting styles of work, held interview workshops, and led field recording projects. We spoke with him about the true power of listening to ー and hearing ー sound and conversation.

Hideki Toyoshima’s Interview Notes

Much of Yoshiaki Nishimura’s writing has “work” or “working” in the title. Nearly all of it comes from interviews; from listening to people’s stories.

In Yoshiaki’s workshops and programs, he doesn’t seem to teach participants anything directly. Instead, he begins by listening to participants’ stories. Yoshiaki also devotes himself to projects that collect the sounds that surround us. Considering these two aspects of his work, we have split this discussion into two parts. The first part explores listening as the awareness of and receptivity to sounds; the second interprets listening as engaging with people’s stories.

I’ve known Yoshiaki for more than 20 years, and I’ve always thought that he resembled a monk. There’s plenty of overlap between his monk-like approach and ultralight hiking, often referred to as Zen hiking. With Yoshiaki’s ideas of listening as a guide, let’s turn our attention to the sounds and the stories of people in the world around us.

Yoshiaki Nishimura Born in Tokyo in 1964, he is the founder of Living World and a planning director and researcher who delves into the different ways that people work. He has written books on work and employment, contributed to the revitalization of Japan’s farflung regions, advised businesses on shifting styles of work, held interview workshops, and overseen field recording projects. We spoke with him about the true power of listening to ー and hearing ー sound and conversation. After graduating from Musashino Art University, he joined the design department of a construction company before starting his own business. His work is wide-ranging: producing websites and museum exhibits; planning and directing design projects; writing books on work and lifestyles; lecturing part-time at Tama Art University and Kyoto Institute of Technology; hosting workshops; and collaborating with local governments and organizations. His books include Creating Your Own Work (2009), Three Days to Think About Your Work (2009), How Do People Work and Live? (2010), Living in the Countryside Today (2011) and Adventuring Together (2018).

The many ways of listening

ーPreviously, you mentioned that when listening to people’s stories, there are two different forms of listening: hearing and listening attentively. Could you explain how you distinguish between these two?

There was a time when I took a year-long training program to become an industrial counselor. During one of the lectures, the instructor introduced active listening — a concept proposed by the clinical psychologist Carl Rogers (*1) ー as a fundamental principle in modern psychology. As part of the discussion, the instructor wrote three different kanji for “listening” (きく) on the blackboard: 聞く (to hear), 聴く (to listen), and 訊く (to ask). The instructor explained that when listening to people, these three forms are often used in different contexts. While hearing (聞く) and listening (聴く) share similar qualities, they are fundamentally different.

But I started wondering: Are they really that different? So I went home and did some research. While looking through Jitō, a character etymology dictionary by the renowned sinologist Shizuka Shirakawa (*2), I discovered that 聞 (to hear) and 聴 (to listen attentively) actually share the same origin. Which made me think: wait a minute, kanji originally came from China, right?

ーRight. What existed in Japan before that was yamatokotoba (native Japanese words).

Exactly. Japan already had yamatokotoba, and the phonetic reading きく (kiku, written in hiragana) existed long before kanji were introduced. That led me to go deeper into the meaning of kiku in yamatokotoba, and I found it absolutely fascinating. Tracing the origins of the word kiku, I discovered connections to other meanings. For instance: when kiku is used to mean a medicine taking effect (薬が効く) or sake having an effect (酒を利く). Listening during an interview is actually closer to how you would taste water or sake. Rather than simply hearing with your ears, you’re absorbing the words and letting them have an effect on your mind and body.

This realization led me to conclude that the most accurate and natural way to express this deeper act of listening is to return to yamatokotoba and write きく, in hiragana, not in kanji, drawing on its broader meaning and use.

(*1)Carl Rogers (1902–1987)

American clinical psychologist and leading figure in humanistic psychology, one of the three major schools of modern psychology. Rogers pioneered client-centered therapy, which forms the foundation of contemporary counseling. He was also the first to use the term “client” instead of “patient” in therapy.

(*2)Shizuka Shirakawa (1910–2006)

Japanese sinologist and professor emeritus at Ritsumeikan University. He dedicated his life to studying ancient Chinese texts and tracing the origins of kanji, meticulously tracking their transformation from oracle bone script to modern characters. He was “an incredible scholar who traced how each kanji evolved over time,” according to Yoshiaki Nishimura.

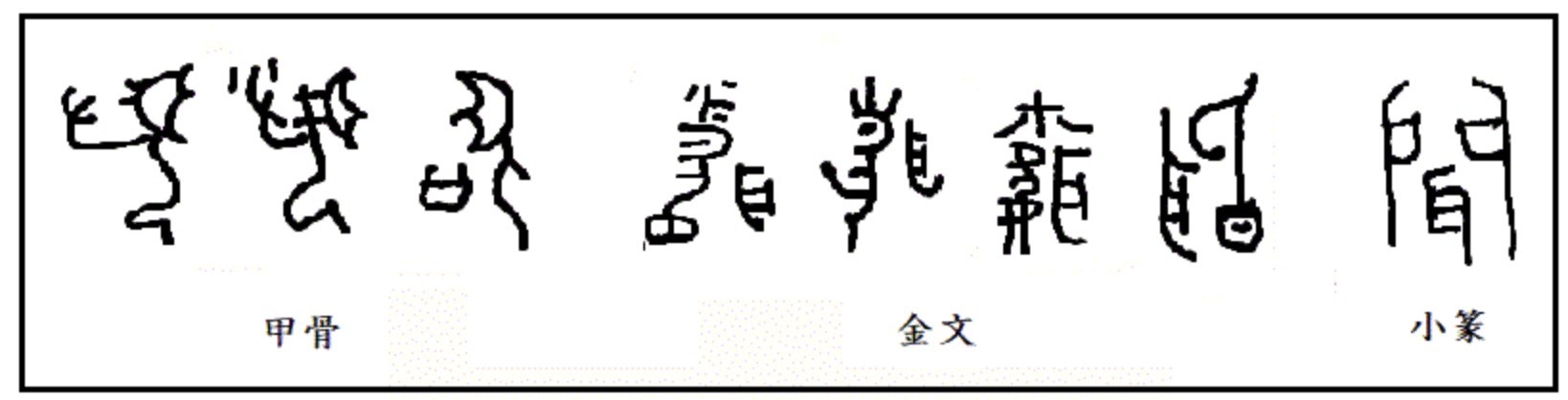

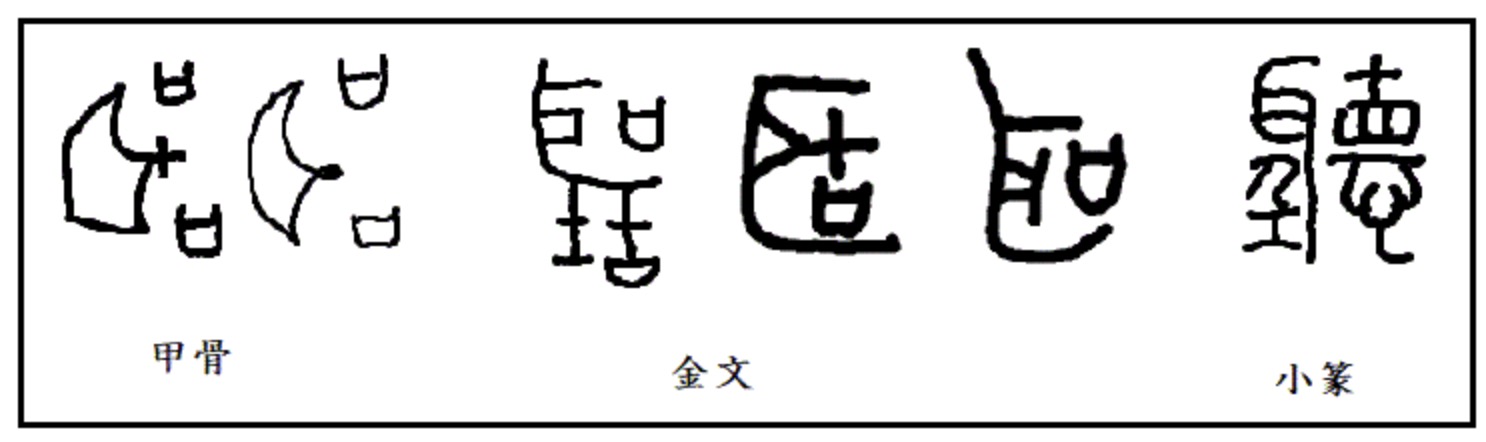

【Excerpt from Shizuka Shirakawa's Jitō kanji character etymology dictionary】

[聞] The phonetic component is 門 (gate). The earliest form of the character, as seen in oracle bone script, depicts a side view of a standing person with an exaggerated ear, symbolizing the act of listening to divine revelations. Another variation shows a hand placed near the mouth, representing 以聞, which conveys the act of reporting or presenting something to the emperor.

[聴] The traditional form of the character is 聽, which consists of the components for ear (耳), 壬 (tei), and the right-side radical of 徳 (virtue). The element 壬 depicts the side profile of a standing person, with a large ear added to signify keen hearing or the ability to listen to divine voices. When the right-side radical of 徳 is replaced with a component (さい) that symbolizes a vessel used for offering prayers, the character becomes 聖 (sacred). A person who stands upright in prayer, capable of hearing the voice or revelations of the divine, is described as 聖 (holy or saintly).

Experiencing the world through sound

ーThe reason I asked for your time today is that I wanted to learn more about the concept of “listening” that you’ve mentioned. You’ve said that there are various ways of interpreting listening to people’s stories, but I also believe there’s a form of listening related to tuning in to sounds. I’d love to hear about both of these kinds of listening. First, could you tell us about Sound Bum (*3), one of your projects, in relation to the meaning of listening by attuning to sound?

Sometime around 1997, just before I started Sound Bum, Microsoft entered Japan, and I was commissioned by them to create content for a web service. At that time, streaming audio technology, known as RealAudio, had just emerged, allowing users to listen to music or audio on the internet without downloading files. It was a time when web services mostly consisted of text and photos, so I thought about creating content that would allow the world to be experienced through sound.

(*3) Sound Bum

A project Yoshiaki Nishimura launched in 1999 with sound designer and field recording technician Yoshihiro Kawasaki. The name Sound Bum refers to a “sound journey” in which participants embarked on a journey to enjoy sounds from around the world. In addition to putting on exhibitions at Japan’s National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, they also produced the CD Traveling with Sounds. On Pioneer’s website, you can go to Sound Bum and listen to travel reports and sound recordings from various locations around the world. (Image credit: Yoshiaki Nishimura)

ーIn 1997, there was still no online video content, right? So, what was the online sound-based experience that you created like?

When you opened the web page, which I had called Sound Explorer, it displayed Earth’s terminator line separating day and night at that moment. In the places where morning was approaching, sunrise sounds played, and where night was approaching, sunset sounds played. I had collected these sounds from around the world. Every time someone accessed the page, they could see where morning was arriving on the planet. I also set up live microphones in several locations, so real-time sounds could be played.

ーIt was sound that was synchronized with the Earth’s rotation! How did you gather all of the sound that you used from around the world?

In London, I went to the British Library Sound Archive, a national repository of 6 million sound recordings and thousands of moving images. Its vast collection of sounds spans wax cylinder recordings (the medium that predated records) to the latest digital recordings. It’s really fascinating. Over several days there, I listened to recordings made, for instance, in Indian forests and islands, and then gathered what I needed. I also recorded sounds on my own that weren’t available in the archive.

ーSo, you actually traveled to gather sound! Did you use your own equipment for field recording?

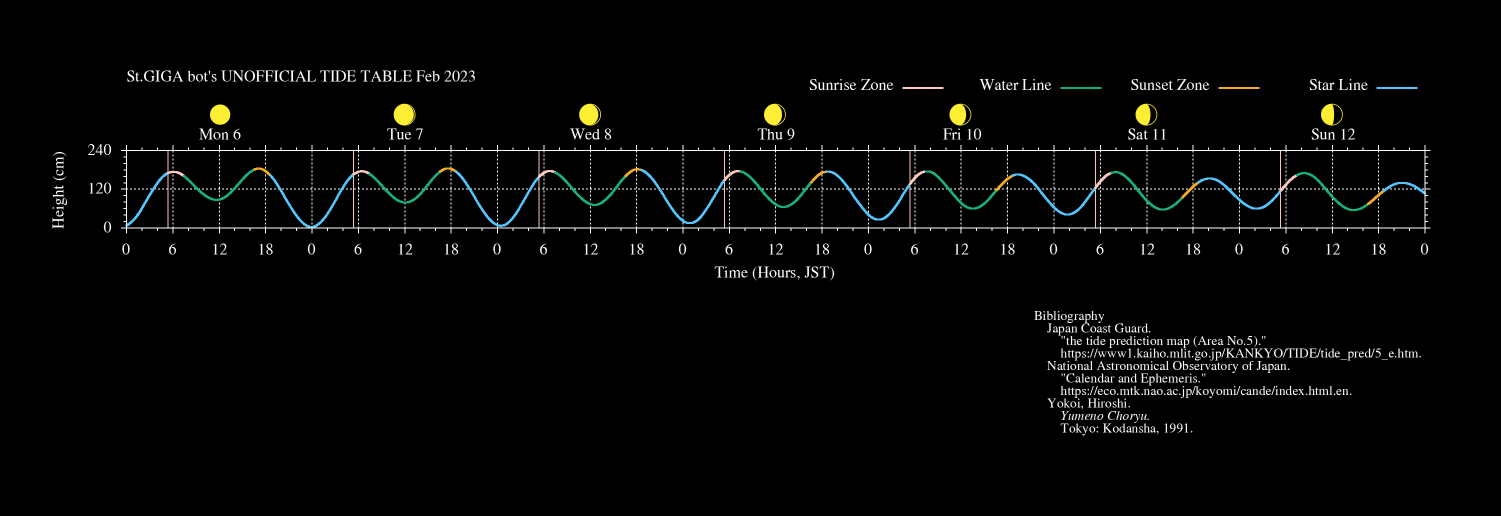

I went on a two-week, around-the-world journey to record the sounds of sunrise and sunset. Joining me for these field recordings was Yoshihiro Kawasaki, a leading sound designer. He had worked at St.GIGA, a satellite radio channel that began on broadcaster WOWOW’s sub-channel, and he was already traveling around the world recording sounds. St.GIGA no longer exists ー it ended in 2003 ー but it was the world’s first satellite-based digital radio station, broadcasting a 24-hour mix of music and natural sounds.

ーSt.GIGA was incredibly innovative, wasn’t it? People still talk about it today. I’m curious: What were St.GIGA broadcasts like?

When you visited the St.GIGA recording studio, there was a timetable on the wall showing the tidal movements. You would see where your shift corresponded to that timetable, and if it was ending around the time when Tokyo Bay would be at high tide, you arranged sounds collected from around the world that would reflect that. During the broadcast, there were narrated interludes: “The sun has just risen in Shiretoko.” Or two hours later: “The sun has risen on Hateruma Island.” It was a soft, gentle narration. I was amazed. I couldn’t believe that this kind of media existed. Back then, every other media outlet would only tell you the time. “It’s now 6:00 am.” Or: “It’s 7:00 am.” There was no other station that gave you the time according to the natural world like this. It was shocking to me.

(Image credit: Yoshiaki Nishimura)

The real-time experience of feeling Earth's rotation

ーI’d love to hear more about your journey around the world collecting sounds. What was that two-week trip like?

It was truly an incredible journey. The arrival of morning is an amazing phenomenon. You can feel different creatures waking up one by one, each on its own clock. For example, when I sat quietly in a forest in a Cuban national park, recording for about three hours while it was still pitch dark, I took in a lot. In the darkness, creatures that sounded like birds made “boo-boo” calls. Then, there was a fleeting moment of silence between night and morning. As the sky began to brighten, a fish splashed in the lake, followed by a bird singing. The birds’ calls changed over time, and then monkeys came through on their patrol.

It was like listening to an orchestra with different instruments joining in, one after another, according to a musical score. And all of this was happening right along the terminator line—the boundary between night and day. I started to imagine Earth turning like a music box, and it amazed me. Even at this very moment, somewhere on the planet, this symphony is playing. The experience was so profound that after returning from the journey, I stopped listening to music. Just opening the window and listening to the outside world felt like enough. I didn’t play a single CD for about a year.

ーThat journey was the beginning of Sound Bum, wasn’t it?

Exactly. Sound Bum was an appeal: travel with a recorder instead of a camera! It wasn’t just about suggesting that doing so would change the quality of one’s experience –– it was an invitation to actually do it. For instance: “Go to Alaska and listen to the sound of the aurora borealis!” You’d be surprised how many people claim to have actually heard the aurora when they visit.

――The sound of the aurora! I’d love to hear it, but does it really make a sound?

It shouldn’t be audible, but about one in four people say they’ve heard it. Some insist: “I swear it wasn’t my imagination ー it crackled like electricity.” Others describe it as a “symphony”. The aurora occurs at an altitude of 80 to 100 kilometers or higher. Even if it were to produce sound waves, the sound should be extremely delayed. Hearing it real-time is impossible. But after listening to many people’s experiences, the only plausible explanation is that they heard something electrical. There’s even a theory that magnetic field lines ー invisible lines representing the direction and strength of a magnetic field extending between Earth’s poles ー affect the brain.

Then, we thought: We won’t know unless we go. A group of about ten of us headed to Alaska. The soundscape of winter there is sparse. Every sound comes through with incredible clarity. You can distinctly hear each living thing, and it gives you the sensation of hearing what’s invisible. Even the distant sound of an Amtrak train was fascinating. It felt like stretching your ears out to distant places.

Sound Bum was a project about expanding our sense of hearing through travel. We conducted it in about 26 locations around the world. We also produced CDs and built a website with the collected sounds, but the real essence of the project was the act of going itself. Carrying a recorder is like bringing a sketchbook ー it changes the way you experience travel. You stay in one place longer, and both the quantity and quality of your experiences deepen.

Traveling the world for the Sound Bum project. (Photo credit: Yoshiaki Nishimura)

ー”Sound Bum” has a really nice ring to it. Did you come up with this yourself? “Bum” refers to a wanderer, right? It also gives the impression of someone completely absorbed in something.

People who live for waves are “surf bums”, and people who live for snow are “ski bums”. Since this was a journey in pursuit of sound, we decided to call it “Sound Bum”. The sound designer I traveled with, Yoshihiro Kawasaki, was a fascinating person. I first met him on Yakushima (a small subtropical island in southwestern Japan whose cedar forest has some of the country’s oldest living trees). He was recording the sound of a stream near Yakusugi Land ー a forest with a number of 1000-year-old Yakushima cedar trees (yakusugi) and well-marked trails winding past them ー and when I listened through his headphones, the sound was incredible. The stream had a loud rushing sound, but the microphone picked up a delicate bubbling. I was shocked that a microphone could capture that. It was like using a magnifying glass!

――I’m curious about how Yoshihiro recorded the sounds. Did he capture the overall environment, or did he focus on specific sounds?

He used a highly directional microphone to pinpoint and capture specific sounds. It was like how the well-known naturalist and ethnologist Kumagusu Minakata (*4) collected fungi while walking through the forest and then examined them under a microscope. I realized that the world is made up of these layers of sound. Later, we hiked together toward the summit of Yakushima’s highest peak, Miyanoura-dake. The places where Kawasaki-san stopped to record weren’t scenic at all. But the natural echoes were beautiful. When I stood next to him, I noticed an incredible balance of sounds surrounding us. That’s when I understood: This is how he experiences the world. It was eye-opening.

ーThe idea of a place with poor views but great sound is intriguing. It feels like adding an extra layer to a map through sound. Just as Minakata used a microscope to reveal an unseen world, microphones can help us tune in to an otherwise imperceptible world. I really understand the appeal of Sound Bum now. From now on, if I reach a mountain summit and it’s whiteout, I’ll make sure to listen carefully.

(*4)Minakata Kumagusu (1867-1941)

A towering figure in Japanese natural history. After dropping out of Tokyo University’s preparatory school, he spent about 14 years traveling and studying abroad in the US and the UK, publishing many research papers. His studies covered a wide range of fields, from mycology (fungi) to humanities.

Listening to people versus listening to sound

ーI’d like to continue our conversation about listening. What is it that fascinates you about listening to sounds?

Memories triggered by photos and memories recalled through sound feel different. When I hear a sound, I don’t just remember the event. I remember the space, the air, even the physical sensations of that moment. I think it’s because vision is selective: You can choose not to look at something. But sound comes from all directions, and you can’t block it out completely. Your hearing is a highly receptive sense, and listening to sound is a deeply immersive experience.

ーThat’s an interesting perspective ー listening as an act of receptivity. But how is listening to a conversation different from listening to the sounds of nature?

Listening to people involves both cognitive and bodily engagement. There’s a fascinating book by Makoto Nakagawa called The Acoustic Universe of Heian-kyo (2004). He describes how people in the ancient capital of Kyoto during Japan’s Heian Period (794-1185) claimed to have heard the sound of a volcanic eruption from Sakurajima, in Kagoshima (around 680 km, or 420 miles, away). Whether they actually heard it is unclear. But what’s fascinating isn’t whether the sound was audible; it’s the fact that they were actively trying to listen to something so far away. They were attuned to distant sounds, stretching their sense of hearing across vast spaces.

When it comes to listening to people, the physical distance between the speaker and listener is much smaller. But listening to the natural world expands the sense of space. That’s the fundamental difference between the two. The act of listening changes the way we perceive our own existence. It broadens the sense of existing here, in this moment.

ーSo when we listen carefully to our surroundings, we’re not just sensing physical space but also expanding our awareness, right?

Sound is vibration. When we speak, we vibrate our vocal cords and the sound resonates in our chest, like the body of a guitar. So when we listen, we’re not just receiving words. We’re physically absorbing the resonance of the voice and sharing the same space. It starts as a vibration, then travels through the air as a wave, and when it reaches the listener’s eardrum or skin, it turns back into vibration. It’s like an analog-to-digital conversion happening in real-time. When we listen closely to a bird perched on a twig, it’s as if we’re extending our ears like a stethoscope to touch the bird’s body, and we enter an expanded state of being.

ーThat makes sense. With sight, we can focus our eyes to see more clearly, but our field of vision still feels limited. It’s not the same as having our eyes extend like our ears do. I now really understand how listening is an act that expands our physical awareness.

I don’t think our sense of self is limited to the surface of our skin. For example, when we ride a bicycle or drive a car, if we consider the tires as part of ourselves, we can directly sense even a small pebble we run over. This awareness changes how we handle the vehicle. Similarly, if someone were to suddenly cut the string of a kite we were flying, it would feel as though a part of us had flown away. In this way, our sense of self isn’t fixed. It stretches and contracts beyond the boundaries of our bodies. Listening to the sounds of nature is a dynamic experience, almost like changing the size of our own being. That’s what makes it so fascinating.