ROGER MCDONALD “Seeing” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

ROGER MCDONALD “Seeing” #1

Composition/Writing: Takuro Watanabe

Editing/Photography: Masaaki Mita

Hiking is an effective way for us to physically engage with, understand and maintain — restore, even — our connection to nature and the world. This is particularly true with ultralight hiking, which by minimizing gear and allowing for longer, more comfortable walks heightens a sense of being in communion with nature.

In the HIKING AS LIBERAL ARTS series, hosted by Hideki Toyoshima, Yamatomichi HLC (Hike Life Community) director, we consider hiking as a liberal art, a field of study that liberates individuals from preconceived notions and norms, empowering them to act based on their own values. This series delves into physical aspects of hiking –– seeing, hearing, eating –– for clues to exploring the value of and potential that extends beyond hiking.

Our first guest is Roger McDonald, an independent curator, founding member of the not-for-profit arts organization Arts Initiative Tokyo and author of DEEP LOOKING: A Guide to Reviving Imagination through Profound Observation (AIT Press). The book explores ways of pulling apart rigid realities with a more deliberate approach to observing art. To learn about the act of truly seeing, we visited Roger’s private museum and art center, Fenberger House, located in Saku City, Nagano Prefecture.

Interview Notes: Hideki Toyoshima

Roger McDonald’s book, DEEP LOOKING: A Guide to Reviving Imagination through Profound Observation, is primarily about art. However, when I tried substituting “Deep Hiking” for “Deep Looking”, I found myself discovering many insightful parallels. Roger’s concept of Deep Looking isn’t just about art criticism or technical discussions on aesthetics — it’s a deeper way of perceiving the world, a tool for navigating contemporary life. This resonates with Yamatomichi’s philosophy. If we shift from merely seeing to actively looking, we may uncover hidden layers of our surroundings and everyday activities. Why not use Roger’s DEEP LOOKING as a map to open your mind and body, and set you on an intellectually enriching path? His approach might transform the way you view your life and the world.

What exactly is “Deep Looking”?

It’s a way of rediscovering what it means to “observe art” as a method for deep meditation, and a technique for adapting to these challenging times. Roger compiled his research and insights into his book, DEEP LOOKING.

DEEP LOOKING: A Guide to Reviving Imagination Through Deep Observation, by Roger McDonald (AIT Press), ¥2,200 + tax (Available on Amazon). Visit the DEEP LOOKING website

Roger McDonald

Born in Tokyo. Educated in the UK from an early age. Roger studied international politics at university and specialized in mysticism (including Zen and psychedelic culture studies) at the University of Kent in Canterbury, where he pursued graduate studies. His doctoral research focused on modern art history and mysticism. After returning to Japan, he worked as an independent curator, organizing and hosting numerous exhibitions. From 2000 to 2013, he also served as a part-time lecturer at various art universities both in Japan and abroad. In 2010, McDonald moved to Saku city, in Nagano prefecture, and in 2014, he opened Fenberger House, where he serves as director. He is also a founding member of the non-profit organization Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT) and director of AIT’s online art course, Total Arts Studies. His book, DEEP LOOKING: A Guide to Reviving Imagination Through Deep Observation, is currently on sale. Fenberger House is listed on Airbnb and can be booked for overnight stays.

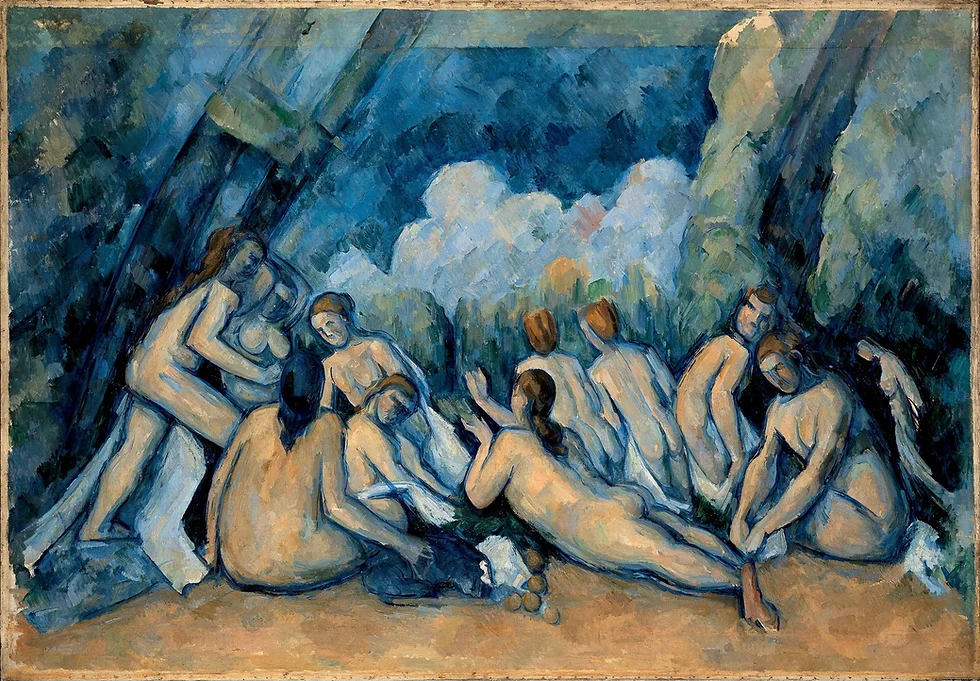

Basic Protocol for "Deep Observation"

The first protocol I’ll introduce is likely something many people have done, at least partially or unconsciously. The key here is to try doing it consciously. You don’t need to imagine anything as complex as aesthetics. Rather, it’s important to avoid being confined by conventional frameworks and to resist the urge to put things into words. Now, if you’re ready, let’s begin.”

(Excerpt from DEEP LOOKING: A Guide to Reviving Imagination Through Deep Observation)

Follow these steps to observe the painting above. Spend about 5 minutes on each one. The timekeeper will signal when the time has elapsed, and everyone will move on to the next phase.

1. Look at the form of the painting and determine what kind of piece it is.

While looking at the painting with as neutral a gaze as possible, slowly confirm its shape and the elements it contains.

2. Link the parts of the painting together.

Carefully observe elements like colors, shapes and materials expressed in the artwork, and start identifying the relationships between each of them.

3. Imagine yourself shrinking and entering the world of the painting.

Try walking inside of the painting. Use your imagination freely and try to create a story within the world of the painting.

4. Share the experience.

If you’re doing this alone, write down what you’ve experienced in your notebook. If you’re in a group, have each person spend about 5 to 6 minutes sharing their experience. Compare your experience with that of others.

ー First, could you tell us about your background?

Roger: I was born in Tokyo. My mother is Japanese, and my father is from Scotland. I lived in Tokyo until I was eight, and then I continued my education in the UK. I went to a boarding school, like Hogwarts from Harry Potter, and then went to university where I majored in international politics. After that, I went to graduate school and studied mysticism, which was a relatively new field in the UK at the time. Looking back, I was deeply immersed in mysticism.

I’ve always loved art as well –– my brother is an artist –– and I had many writer friends, so my interest in the intersection of religious studies and art was natural. At that time, there weren’t many researching the field, and my work on mysticism and art was often ridiculed. However, I was fortunate to have good professors and was able to finish writing my thesis.

After returning to Japan, I worked as a freelance curator. I joined the office of Fumio Nanjo, who was director of the Mori Art Museum at the time, and was involved in the Yokohama Triennale. I had some personal curation projects and began teaching at universities. I was always working in the art world, but I also felt that I didn’t really fit. For example, at large international exhibitions, there were so many artists and the budgets were so large. I ended up witnessing some of the unpleasant side of the art world. It was an amazing experience, but I think deep down I was more of a researcher than a curator. As much as I enjoyed it, I felt that I wouldn’t stay for long.

What the Fenberger House Aimed to Achieve

ー Did you create Fenberger House because of your experience and limitations within the world of art museums and biennales?

Roger: Yes, I felt personally limited in the world of big museums and biennales. So, I created Fenberger House as a place where I could conduct various experiments and have my ideal art experience. Fenberger was a pen name I used when I wrote poetry as a university student. It’s essentially a museum for a fictional character.

What I want to do here includes, first, the intersection of mysticism and art, which as I mentioned was a research theme of mine. It’s something that’s not very common in the art world, so I’ve been organizing small exhibitions around it. The second aspect is hosting art viewing sessions where we practice “Deep Looking.”

To put it bluntly, I believe exhibitions are devices that manipulate the quality of the viewer’s experience. I’ve been experimenting with how to create that quality in my own exhibitions. One example of this experiment is a long-duration viewing experience. It’s reservation-only. I personally pick up the visitors from the nearest train station. They stay for about six hours at Fenberger House and fully engage with the art. I jokingly call it a “kidnapping”. It’s not just about quickly viewing the art, passing through a gift shop, and having a drink at the café like in today’s museums, which is more aligned with the tourism industry. I think there are different ways to engage with and appreciate art.

When I studied religion, I realized that, before modern times, there were many immersive art experiences. I always wondered why contemporary museums weren’t offering more diverse experiences. Almost everywhere you go, you see the same pattern: viewing art in white-walled rooms and then passing through a gift shop, with a quick stop at a café. It’s very much a modern manifestation and has become quite singular. But, for example, in Gamelan music performances, which can last around 10 hours, the audience can sleep, eat and listen while the performance continues. I believe art can also alter our consciousness. I’ve always disliked how something that should be diverse has become so limited. Fenberger House is a place to experiment with different methods of art appreciation; in a sense, it’s a research center.

ー Earlier, you mentioned that reading DEEP LOOKING as a hiking book was really interesting, and I agree. Hiking is a physical activity. You walk continuously, listen to birds and water, feel the wind, and sometimes find yourself in a meditative state. It engages all of your senses. Hiking, in which you immerse yourself in nature with a slightly trance-like awareness, aligns perfectly with the ideas in DEEP LOOKING.

Roger: For me, the concept of “physicality” is very important, and I want to reinstate the idea of viewing through the body. In contemporary art appreciation, the focus tends to be on the retina. We often understand art through the very narrow area of the retina and brain, but I think that’s a mistake. Stopping and viewing a work of art from the body, rather than just through the eyes, is a way to open up that narrow circuit again. That’s why physicality becomes so important.

ー In DEEP LOOKING, you mention that “an extraordinary state of consciousness is effective for freeing oneself from rigid, habitual thinking and for thinking creatively.” I’d love to hear more about this, and about the idea that “intentionally setting aside non-productive time has immeasurable value.” I also feel that the act of hiking, like looking at a painting for hours, holds tremendous value, even though it doesn’t generate any money.

Roger: Consciousness is not fixed; it doesn’t stay the same all the time. When we sleep, we naturally enter a different state of consciousness, and when we dream, it’s another. Even when we idly look out of a train window, our consciousness subtly shifts. Our awareness constantly expands, contracts, becomes rigid, or loosens. With that as the foundation, everything around us — whether we’re looking at art, listening to music, or drinking coffee — becomes a tool that gradually alters our consciousness.

What DEEP LOOKING is suggesting is that looking at art has always been a powerful act that loosens our consciousness. However, like on Instagram, where you passively view something, nothing will happen unless we actively engage with some level of literacy and energy. It’s not as simple as just casually looking and expecting something to occur. We must be prepared and accept the risk in the process.

Looking at art isn’t always positive, safe or wonderful. When you truly start to observe, it can shake up your unconscious, physical state or psychological condition. Some people cry in museums, others get angry. Sometimes, people may even experience temporary emotional instability. Art holds that potential. The process that leads to this intense experience is what “Deep Looking” is about, and the book serves as a guide for it. In today’s world, where art is increasingly reduced to a form of leisure or entertainment, DEEP LOOKING serves as a counterpoint to the loss of the profound and powerful elements that art used to have.

ー Do you think the reason art has become commodified as part of the leisure industry is due to its separation from faith?

Roger: I think that’s a big part of it. It’s the separation from faith and ritual. Going to a museum is a secular experience that is detached from the faith and ritual associated with sacred spaces. It’s almost closer to the realm of science. That’s why curators wear white gloves when handling art. For example, when you visit an artist’s studio, the artwork is spread around in a completely different way. The work often is casually touched, placed on the floor, or put against the walls. In the studio, the artwork is still closely tied to daily life. But as soon as you step out of the studio, you enter the white-gloved zone, where it feels like you have to be cautious.

Unfortunately, museums have done away with these other elements in order to present the art in a very sanitized, detached way. So, the question is: How can we reconnect these aspects? I think we can do so by having the viewer bring a certain level of skill and literacy to the viewing. DEEP LOOKING is a guide for that purpose.

ー Churches and temples, even when you set aside their religious aspect, also functioned as spaces that served such a role. The “cave” mentioned in DEEP LOOKING is another important element in this context.

Roger: For me, caves represent an archetypal art environment. Caves hold the oldest traces of human expression discovered on Earth — paintings that Homo sapiens left behind around 40,000 years ago. What’s mysterious is why the paintings are not near the entrance, but deep within the cave. Why would someone undertake such a difficult journey, into the dark recesses of the cave, to create murals? Why would they venture into the belly of the Earth to leave an expression behind? This is very romantic to me. I consider the cave to be the prototype of the museum. Museums should not forget about caves, but modern and contemporary museums are spaces that have detached themselves from caves. They emphasize transparency.

A good example is the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, which is built entirely with glass, bathed in uniform, bright light. It’s the opposite of the deep, mysterious space of a cave. Modern museums are expansive, bright and transparent, conveying the idea that everything can be understood through reason. But I think we should not forget the cave-like elements of a museum. When I think about how we can bring those elements back to today’s museums, perhaps we can reclaim them through the act of DEEP LOOKING, with the viewer restoring that connection.

Flow State and Altered States of Consciousness

ー Starting with the cave, and moving on to churches and temples, I believe these spaces, which shake up our consciousness, physicality and mental states, serve a similar function. Flow state (the state of being immersed in an activity, forgetting the self) seems to occur often during hiking. How do you interpret the flow state in relation to DEEP LOOKING?

Roger: When you observe art deeply, you naturally enter an altered state of consciousness, similar to that of a child engrossed in play or a person meditating. Flow state is the term I use to describe this. In the US, it’s often mentioned, and it’s widely applied in business as well. Companies like Google research how to bring employees into a flow state –– when they’re deeply immersed in something. There are even workshops and training programs for it, which is typical of the approach in the US. I think most people have experienced it at least once in their lives.

ー “Altered states of consciousness” are important in the practice of DEEP LOOKING. Could you explain what you mean by this?

Roger: Altered states are changes in our usual conscious state, the one we spend most of our time in. For example, when we’re in a rational, communicative state, we’re able to listen, respond, use language, and think logically. Then suddenly, for some reason, that state shifts significantly. Dreaming is one example of an altered state, and so is flow state.

Looking at human civilization, altered states have often been used in special rituals. Before institutionalized religions emerged, most cultures had shamanistic practices. I read in South American literature that, in shamanism, a good shaman can radically alter their consciousness, though that alone isn’t enough. A good shaman must also be able to return to their baseline state after the altered experience, and then share the wisdom they gained with their community. Only then are they considered a true shaman.

I think this is absolutely true. If someone stays permanently in that altered state, they would end up in a mental institution. What’s important is, as I mentioned earlier, returning to the baseline, digesting what you’ve experienced, seen, and heard, and then sharing it as new ideas with your community. This is how the community strengthens and heals. This is a very important point when talking about altered states of consciousness.

Just saying, “Let’s trip out (using drugs to induce a hallucinatory state),” seems irresponsible and dangerous. Recently, there’s been a re-evaluation of the 1960s counterculture in English-speaking countries, and there’s a lot of debate about psychedelic culture. Figures like Timothy Leary* tried experiments like the acid tests — taking LSD and easily altering consciousness with the hope that it would lead to social change — but they did these experiments without proper guidance, and, as expected, many people ended up in mental institutions.

ー That seems, to me, a very important point. In hiking, just like in altered states of consciousness, you need to not only go into a different state of awareness but also return from it.

Roger: Yes, and at the same time, I think it’s important not to simply reject the 1960s psychedelic counterculture, but to seriously reconsider it. A figure who can provide some insight here is the British political theorist Mark Fisher**. He identified three important forms of alternative political and social practices that arose in response to the crisis of neoliberalism in the 1960s and 70s: “class consciousness”, “psychedelic consciousness” and “consciousness reform workshops.”

The story that neoliberalism tells is: “Reality is fixed, and we must adapt and accept our fate.” This is connected to the resignation that many people feel today. According to Fisher, “psychedelic consciousness” is connected to what 19th-century Canadian spiritual researcher Richard Maurice Bucke*** described as “cosmic consciousness”, which opposes the ideas of neoliberalism.

*1 Timothy Leary

American psychologist and former Harvard University professor (1920-1996). In the 1960s, he conducted research on personality transformation through hallucinogenic substances like LSD, claiming that these substances could induce brainwashing and advocating for the freedom of consciousness. In his later years, he compared computers to LSD, proposing the idea of using computers to reprogram the brain.

**2 Mark Fisher

British critic and political theorist (1968-2017). After earning his PhD at the University of Warwick, Fisher served as a guest researcher and lecturer at the University of Continuing Education and Goldsmiths College’s Department of Visual Cultures. He expanded on music theory, cultural theory and social criticism on his blog “K-PUNK.” His works include Capitalist Realism, Ghosts of My Life and The Weird and the Eerie.

***3 Richard Maurice Bucke

Canadian physician, psychiatrist and philosopher (1837-1902). In 1872, Bucke experienced a mystical experience in which he vividly felt the universe as a living being. He named this sensation “cosmic consciousness” and studied an array of these experiences across time and cultures. In 1901, he published Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind. He positioned “cosmic consciousness” as the next stage in human development and hypothesized that it would eventually spread globally.

Hiking Prescribed as Therapy

ー One of the roles of society and communities is to take care of each other. If someone has an extreme experience, it’s important for everyone to watch over and care for that person.

Roger: This kind of care is deeply rooted in Indian culture. In India, you can find “sadhu” — highly enlightened Hindu ascetics who wander around naked without any possessions or money. But these people are valued, and the community cares for them. This culture of caring for those without material wealth, yet still being considered important, has existed in India for thousands of years. It’s remarkable to think that in the modern world, a person walking around naked without money might still be seen as valuable. It seems that various states of consciousness coexist in India. In today’s world, we have specialists like psychiatrists or psychologists. For example, if someone in a country other than India were walking around naked claiming enlightenment, they might be told, “You should take this medication.” That cultural difference is quite extraordinary.

Today, there’s the concept of “social prescribing”. Particularly in Scandinavian countries, activities like art appreciation or hiking are prescribed as therapy to treat mental health issues, instead of medication. A system exists in which a doctor might write a prescription that says: You must walk for one hour every day for a week. In the UK, social prescribing is part of the healthcare system. This might be how the therapeutic potential of art gets reevaluated and recognized for its importance. In this sense, hiking –– and the act of walking –– is really important.