Lecture 2: Thinking About Walking ー Shoes

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

Lecture 2: Thinking About Walking ー Shoes

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

Tomoya Tsuchiya, owner of Hiker’s Depot in Tokyo and one of Japan’s ultralight hiking pioneers, is the author of Ultralight Hiking (2011) and a frequent Yamatomichi collaborator. Every few months, Tsuchiya will host a lecture at Yamatomichi’s Laboratory, in Kamakura, covering the history of ultralight hiking and the evolution of its practitioners’ gear, from packs and tents to shoes and sleeping bags. His first lectures explored the birth of ultralight hiking backpacks in the late 1990s; their evolution over the past quarter century; and structural details of backpack design. In this second lecture series, Tsuchiya discusses the evolution of footwear, from mountaineering boots to trail running shoes; shoe structure and design; and the mechanics of walking.

Introduction

In the first lecture series, I talked about the history of ultralight hiking as seen through the changes in backpack design and covered the basics of carrying ultralight backpacks. Walking is also crucial. Which is why, for this second lecture series, I will focus on shoes.

Tomoya Tsuchiya, owner of Hiker’s Depot in Tokyo, one of Japan’s ultralight hiking pioneers and author of Ultralight Hiking (2011).

In ultralight hiking, wearing shoes that resemble trail running models, rather than traditional mountain boots, is now the norm.

Anyone who has experience with conventional hiking might have worn boots. In the past decade, many people with ultralight gear started off wearing trail running shoes. This raised concerns. Is it a good idea to wear trail running shoes instead of hiking boots? Anyone who has been wearing trail running shoes will say: Yes, they’re fine. But understanding the differences between traditional hiking boots and trail running shoes, and the reasons there aren’t problems substituting the former for the latter –– beyond personal experience –– can deepen your interest in walking.

Footwear on display, from high-cut hiking boots owned by Tsuchiya-san and the staff to the latest trail running shoes.

The Birth of Hiking Boots

First off, let’s talk about how hiking boots were developed.

La Sportiva Nepal Evo GTX, a model representing modern heavy-duty mountaineering boots for snowy peaks.

This is an example of what we refer to as a hiking boot. Leather hiking boots were originally designed for the rocky and icy terrain of the European Alps, not just for rocky trails but for off-trail areas with rugged rock formations and icy slopes on snow-covered mountains.

When these hiking boots first came out, crampons hadn’t yet become what they are today, so in snowy mountains, climbers relied on ice axes to cut footholds during ascents. It was rare for climbers to place a foot flat on a surface, and they often used traction near the toe of the shoe. In that case, the hardness of the sole –– which was directly linked to toe rigidity –– was crucial.

Stiff-soled hiking boots allow you to transfer power to your toes even when raising your heel, enabling you to press into the ground.

When wearing shoes with a softer sole, you need to grip with your toes, which can lead to fatigue and strain because you’re constantly lifting your heels and using the strength of your calf muscles. On the other hand, a stiff sole gives you solid support when standing on an unstable foothold with your toes, reducing foot fatigue.

If your ankle moves around too much, it can tire out your core and destabilize your body. High-cut hiking boots limit the ankle’s range of motion, which in turn helps with stability. Maintaining body stability in snowy or rocky conditions while minimizing foot fatigue is key. Hiking boots are specifically designed for this, which is one advantage of wearing them.

When climbing on snow or rocky terrain with small footholds, the high-cut boots and stiff soles help support your body weight.

The main reason that traditional hiking boots were recommended for people who were new to mountain climbing was the long-held assumption in Japan’s climbing industry that equated climbing with scaling mountains in winter.

In 1956, Japan experienced a surge of interest in mountaineering, after a Japanese team, led by Yuko Maki, made the first successful ascent of Mt. Manaslu (the world’s eighth-highest mountain and an 8,000-meter peak) in the Himalayan mountains of Nepal. That achievement brought national attention to alpinists’ pursuits. At the time, the Japan Mountaineering Association –– consisting of university alpine clubs, professional climbers and recreation climbing by social groups –– set a goal of more difficult, higher-elevation climbs in Japan and overseas.

At higher elevations, climbing rock and ice was common, so mountaineering shops typically recommended boots with stiff soles and firm ankle support. However, these are not ideal for walking, and are restrictive in the same way that ski boots can be.

Old-School Alpine Footwear: Tabi (Split-Toe Socks) and Straw Sandals

Even after modern, European-style hiking boots were introduced in Japan, alpine guides in Japan’s Northern Alps continued wearing tabi with straw sandals in non-snowy conditions.

In my book, Ultralight Hiking, I mentioned this: Jūji Tanabe*, who later became a prominent figure in the Japan Alpine Club, criticized hiking boots, saying they restricted movement. When hiking in places where there’s no snow, it’s easier to walk when your ankles can move freely.

*Tanabe (1884-1972) was an alpinist and English literature scholar. He began mountaineering as a university student and wrote travelogues about the Japanese Alps and Chichibu mountains, including Mountains and Valleys and Passes and Highlands.

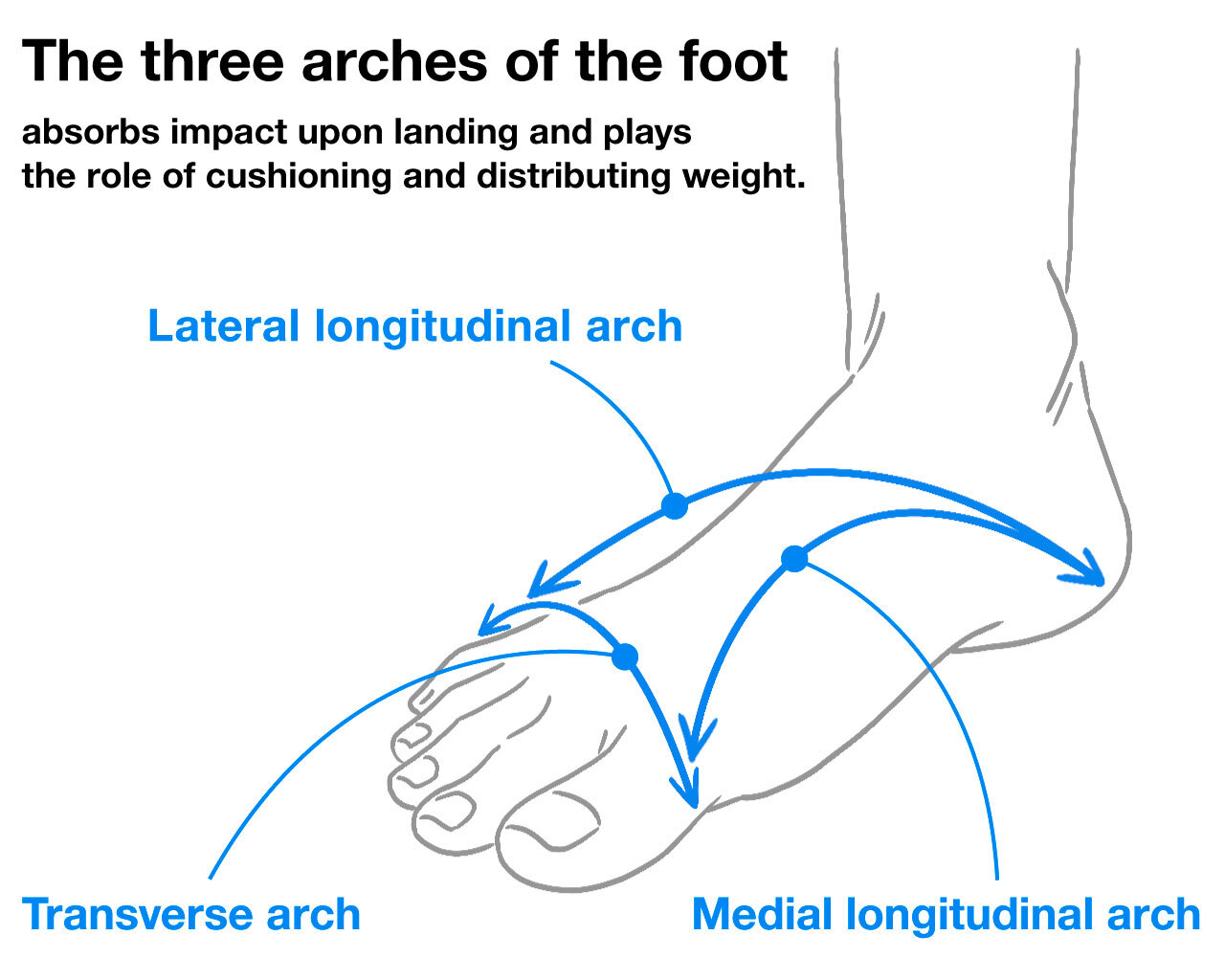

This is because the human foot has three arches: the transverse arch, medial longitudinal arch and lateral longitudinal arch. These act as natural cushions that absorb impact from the ground and distribute the load.

The front part of your foot is used for pushing off. When you stand, your body weight is supported primarily by your heel. If completely immobilized in a shoe, your foot can support and distribute weight, but it has a hard time pushing off.

With more freedom to move the ankle and a soft shoe sole, it’s easier to perform actions like pushing off while walking.

Because of this, even though alpinists of the past understood the advantages of mountain boots, they also believed footwear with more freedom, like tabi (split-toe socks) or waraji (straw sandals), made for better walking in non-snowy conditions. When I was a university student 30 years ago, we wore mountain boots during group expeditions but preferred jogging shoes while hiking on our own.

The upperclassmen who went stream climbing wore water shoes for the ascent, but for the descent, switched to simple, Velcro-fastened shoes that had grip and allowed them to run downhill. Some, including those in the group who were into rock climbing, used ordinary sneakers to climb mountains in summer instead of climbing shoes. Which is to say that low-cut jogging shoes have been commonly worn in the mountains for some time.

Ultralight-Inspired Low-Cut Shoes

Back when “backpacking” was a common term in the US, people shouldered all of their essentials –– usually 20 to 40 kg of gear. I mentioned this in the previous lecture series on backpacks. For support, hikers wore mountain boots. But the heavy gear made walking exhausting and increased the likelihood of injury.

As an alternative to this, Ray Jardine* came up with the “Ray-Way”, his methodology for long-distance hiking

(*Ray Jardine, known as the father of ultralight hiking, wrote Beyond Backpacking (later revised as Trail Life), which outlined his methodology for long-distance hiking. It continues to influence many ultralight hikers. Ray also sold DIY kits for backpacks and tarps, laying the foundation for the Make Your Own Gear (MYOG) culture.)

What kind of shoes did Ray wear when he reduced his backpack’s total weight to 7 to 8 kg? He opted for what back then were called “tennies” (tennis shoes) or jogging shoes with modified tongues. Reducing the weight of his pack also cut down the strain on his body, so he no longer had to wear heavy mountain boots. Getting around in regular shoes was a lot more comfortable.

Tsuchiya makes his point about the shoe’s tongue.

Ray cut the shoe tongue to improve breathability. I’ve tried this on my own shoes but it was painful when the laces dug into my foot. This kind of experimental mindset was the essence of the

“Ray-Way” and the ultralight philosophy that his methods spawned.

In the US, people were choosing low-cut shoes like running shoes over traditional mountain boots, a shift that was driven by the “Ray-Way” and the ultralight movement that followed.

Ever-Lighter: Trail Running Shoes

As I mentioned, there are two key differences between mountain boots and low-cut shoes: the stiffness of the sole and the range of ankle movement. Low-cut shoes feature soft soles and allow for free ankle movement, so the wearer can walk naturally. Long-distance hikers who prioritized lighter weight favored low-cut shoes.

In the low-cut shoe category, there are many options: lightweight; zero-drop shoes and barefoot shoes; and so-called approach shoes, which have slightly stiffer soles that are useful on rocky terrain.

La Sportiva’s TX Guide combines the performance of both trail running and approach shoes.

Even when you put your weight on the toe, the sole won’t bend due to its stiffness.

In 1997, after changing its name from One Sport, Montrail was the first brand to develop trail running shoes that differed from road running models. In the 2000s, the shoes most widely used by ultralight hikers were probably the Montrail Continental Divide and Hardrock models (Montrail was acquired by Columbia Sportswear in 2006). What set these trail running shoes apart from today’s models was their durable protection. Back then, the emphasis was on ensuring that trail running shoes gripped well and didn’t fall apart over long distances. This was meant to address one of the drawbacks of wearing road running shoes on trails.

The Montrail Continental Divide was an iconic shoe that symbolized ultralight hiking in the 2000s.

Montrail Hardrock, known for its tougher build compared to the Continental Divide, was also widely loved by many hikers.

The Hardrock’s sole came with a rock plate and was significantly stiffer than today’s trail running shoes.

At the time, Montrail shoes came with rock plates in the soles. These plates were designed to reduce the impact from the ground while adding a stiffness similar to that of mountaineering boots. In fact, the Montrail Hardrock was made to endure the Hardrock 100, a 100-mile ultramarathon in the US. Its design made it significantly heavier than today’s trail running shoes. In the 2000s, other models –– the La Sportiva Wildcat Mountain Running Shoe, for instance –– were also highly regarded for their durability as trail running shoes.

Many people who enjoyed trail running were also into hiking and mountaineering; even more of them were runners or joggers looking for a new challenge as participants in trail running races. To target this crowd, running shoe brands began developing models for trails in addition to their standard lineup.

Outdoor shoe brands and running shoe brands had a very different approach, which was most evident in upper durability and sole stiffness. Outdoor shoe brands applied their expertise in trekking boots, prioritizing protection over weight reduction. Meanwhile, running shoe brands designed their models for racing, which meant lighter uppers and soles but less durability. This explains why many trail runners have had the uppers of their shoes wear out before the soles.

Today’s trail runners typically don’t shoulder heavy loads during races, and there are usually plenty of aid stations along routes. As a result, runners can focus on speed –– and don’t need sturdy shoes. If their shoes fall apart mid-race, they can change into a new pair at drop points along the route. This is one reason that trail running shoes have become lighter in weight and more geared toward running.

Montrail trail running shoes were considered too heavy for anyone who wanted to run fast. That’s resulted in a shift among outdoor brands toward trail running shoes with softer soles that more closely resemble conventional running shoes.

Even within the trail running shoe category, you can see the difference in upper thickness between those developed with an outdoor shoe approach (left) and with a running shoe approach (right).

Then there are the so-called barefoot shoes. Vivobarefoot and Xero Shoes design their models so you experience the feeling of walking or running barefoot. These shoes can be very effective, if you understand their benefits. But they don’t offer much protection. How you move matters and can make a difference in preventing injuries. After a number of brands released barefoot shoes in the mid-2000s, lawsuits in the US over some models undermined demand and made brands wary.

Lately, barefoot shoes have had a resurgence, with Vivobarefoot and sandal makers* like Huaraches and Luna Sandals rolling out new models. These shoes are fantastic for those who more consciously want to explore the mechanics of walking. And I’m happy to see this understanding gaining traction in Japan.

*The Rarámuri, a group of indigenous farmers in Mexico (called Tarahumara in Spanish) known for their ancient footracing traditions and startling ultramarathon finishes, ran in sandals made with leather straps and soles from old tires that were cut to fit the shape of their feet. Their footwear inspired barefoot sandals made by the likes of Luna Sandals.

Xero Shoes’ Mesa Trail is a flat “zero-drop” shoe that mimics the feeling of walking barefooted.

This shift towards low-cut shoes –– running shoes and trail running shoes –– that are better suited for walking has had a big influence on the sector, spurring the evolution of trail running shoes to more closely resemble conventional running shoes. It’s important to understand this transformation in footwear in today’s long-distance and ultralight hiking scene.

Choosing Shoes Based on Pack Weight

Many of you have probably asked in stores which shoes are recommended for different pack weights. Ultimately, your own fitness and strength play a role. Take pack weight, which is the total weight of everything you’re carrying, including water, food, and fuel, and is broken down into categories –– 8 kg, 12 kg and 15 kg and over, for instance. Almost any shoes should work when carrying a pack weighing up to 8 kg. Getting your pack to weigh less than that should be the goal if you want to wear barefoot shoes like Vivobarefoot or Xero Shoes or lightweight trail running shoes. That will allow you to get the most enjoyment out of these kinds of footwear. For Yamatomichi users, this is roughly equivalent to tent camping with the MINI pack.

With a pack weighing 15 kg or more and low-cut shoes, you will put significant strain on your muscles and stamina because of the energy that will go toward stabilizing your ankles. If that’s your pack weight and you’re mountain trails with unstable ground that forces you to be on your toes frequently, I recommend high-cut or stiff-soled shoes, which should help spare your calf muscles from exhaustion.

Yamatomichi users are more likely carrying packs weighing between 8 kg and 12 kg. You might have a base weight of around 5 to 6 kg, plus 2 to 3 liters of water and food, for a total of more than 10 kg. If that’s the case, you’ll want shoes with more protection and a stiffer sole, similar to the early Montrail models. These will allow you to carry that weight more comfortably.

Tsuchiya recommends lightweight shoes when carrying packs weighing up to 8 kg. For packs weighing 15 kg or more, high-cut, stiff-soled hiking boots work better. For something in between, around 10 kg, trail running shoes with good protection and stiffer soles work well.

This middle category of shoes isn’t as easy to find. In the US, La Sportiva’s Wildcat comes close but isn’t widely available in other markets. Recently, Topo released the Traverse, which is similar to the early Montrail models and is billed as a long-distance trail model.

Japanese brands ASICS and Mizuno sell models for trail running that are worth considering. ASICS’s GEL-Fuji is designed for Japan’s Fuji Mountain Race, held in July on and around Mt. Fuji and combining elements of an urban road race, cross-country course and mountain trail race. These shoes have a moderately thick sole, solid toe and heel cups and reinforced toes, and aren’t the only ASICS with these features.

We’ve reached the end of our first session covering the birth of hiking boots and the evolution of trail running shoes. In the second session, we’ll discuss proper fitting for trail running shoes.

YouTube

Watch the lecture on video!