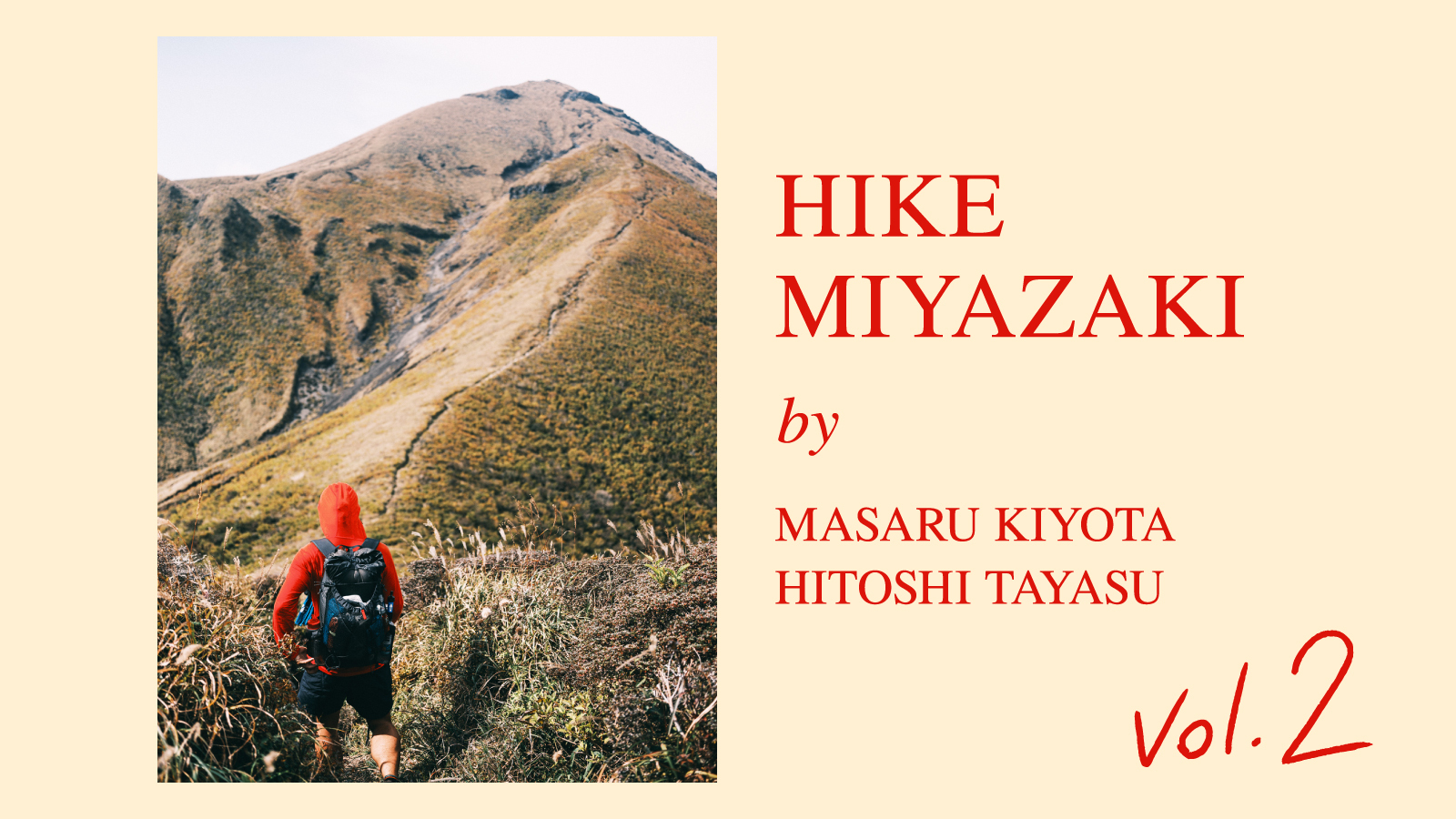

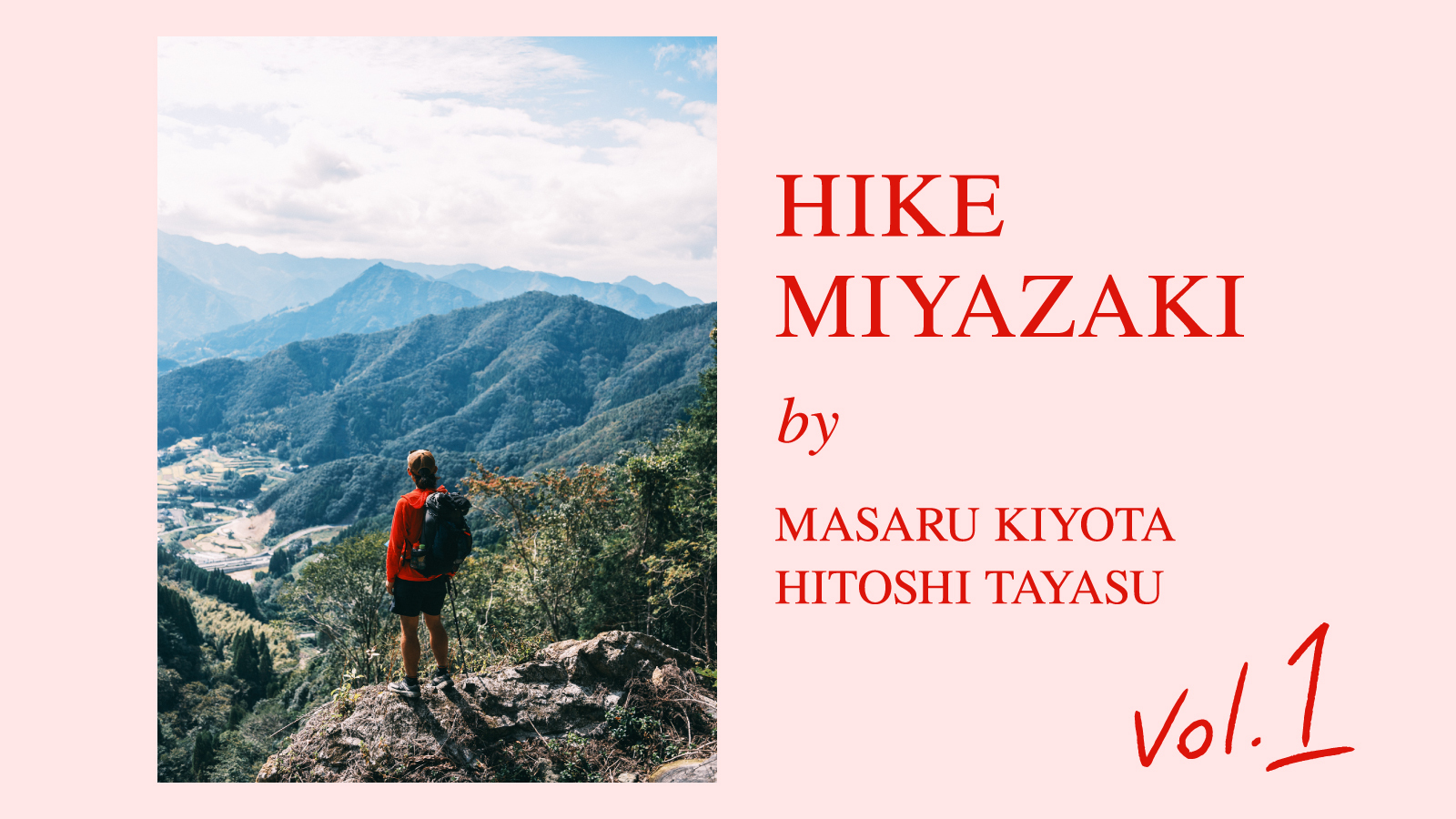

Kyushu Nature Trail: Miyazaki Section – Vol. 2

Photos: Hitoshi Tayasu

Kyushu Nature Trail: Miyazaki Section – Vol. 2

Photos: Hitoshi Tayasu

Ever heard of Japan’s Long-Distance Nature Trails? First conceived by the Ministry of the Environment in the 1970s and developed by the national and regional governments, the trails span eight sections, connecting parts of northeastern and southwestern Japan on three of the four main islands: Tohoku, Tokyo Metropolitan Area, Tokai, Chubu-Hokuriku, Chugoku, Kinki, Kyushu and Shikoku. Two more –– the Hokkaido Nature Trail, in the northernmost main island, and the Tohoku Pacific Coast Nature Trail –– are in the works. In theory, a thru-hiker will one day be able to walk 27,000 km of trails. But in reality, many sections aren’t well-maintained, and not many hikers who go on to complete the Tokai Nature Trail, linking the two major commercial centers of Tokyo and Osaka, share much about their experiences.

This is the second part of long-trail hiker and Yamatomichi Journals contributor Masaru Kiyota’s walk along the Miyazaki section (350 km) of the Kyushu Nature Trail. His journey offers evidence that a long-trail culture has taken root in Japan.

Read the first part here: HIKE MIYAZAKI Kyushu Nature Trail: Miyazaki Section – Vol. 1

Pleasant Morning, Pleasant People

“Shall we sleep here tonight?”

Under a highway overpass, Hitoshi and I laid out our mats and sleeping bags. On a walking journey like this, you never know where you’ll find a place to bed down for the night. Our search took place daily, before sunset, while we walked.

That evening, as the sky darkened, the sun-warmed concrete beneath us cooled, and we fell asleep. At some point, in the middle of the night, I was woken by Hitoshi’s snoring echoing off the overpass. How could anyone make such a racket while sleeping? I opened my eyes, but as I turned to look at him, I saw something else: a sky packed with starry pinpricks.

The towering man-made highway against the vast universe of stars made for a strange, captivating juxtaposition of the artificial and celestial. I tried to get back to sleep but my buddy’s snoring made that next to impossible. At 06:00, the sun rose –– later than what I was used to in Osaka, to the east of where I was now.

I pulled out my phone. I was scrolling through my social media accounts, when I noticed a new message: “Good morning! I’d like to bring you breakfast. Is that possible?”

I turned to Hitoshi. “Hey, it looks like someone wants to bring us breakfast!”

“Really? Amazing!”

“Looks like they’re from Oita (prefecture)!” I said.

“When are they coming?”

“Not sure. But we’re in no rush, so let’s wait!”

Thirty minutes later, a man approached us. At this hour and in this place, he could only have been there to see us. I waved enthusiastically.

“Nice to meet you!” He greeted us cheerfully, and handed over a McDonald’s bag and a Coke. A real-life trail angel! We’d been lounging around but the sight of food immediately revived us. We thanked him and immediately dug in.

Daisuke was the name of our trail angel. As we devoured our burgers, he fished out something from his bag.

“Actually, I received these postcards from you two a while back!” Daisuke said, holding up four postcards.

Hitoshi had sent one from the PCT in the US, and I had sent three. Among them was a postcard from the Hideaki Anno exhibition titled “Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time”. I had no idea what I was thinking when I sent that.

You’re probably wondering: What’s with the postcards? Everywhere I travel, I send postcards to people who have reached out to me on social media. Since I started this in 2019, I’ve written more than 1,000 postcards. For me, these random missives create bonds that I’m incredibly grateful for. I feel somewhat embarrassed at the thought of my unpolished handwritten messages reaching all of these people, and yet it also excites me to think that one day I might come face-to-face with some of them.

Daisuke had driven for hours to meet us. To bring us this food. I was so very grateful.

And then, another voice: “Masaru!! Good morning!!”

It was Tani. He had driven from the neighboring prefecture of Kumamoto. He’d previously mentioned that he would try to swing by while we were on our long walk.

“Wow! Tani, you made it!”

“I found you guys right away!” he said.

“I suppose there’s no one else under the highway overpass at this hour,” I said.

“Trail magic!” he said. These words were written on top of the small cooler box that he’d filled with beers and soda for us.

On long trails in the US, trail angels are people who generously deliver what’s known as trail magic –– food, drink and other items that are meant to lift hikers’ spirits. We’d just finished our McDonald’s breakfast and Coke, but we couldn’t resist cracking open a beer. There we were beneath a highway in rural Miyazaki, drinking beers together at dawn, hours before most children would leave for school.

It’s moments like these that make walking a trail worthwhile. These unexpected twists are what remain etched in my mind, long after memories of breathtaking landscapes have faded. They’re small, compared to significant, life-changing events. But I cherish these simple acts.

Tani is a hiker who has walked thousands of km of long trails in the US. There are many hikers like him who are genuinely pleasant and kind. Whether they were always like that or became that way once they started their long walks, I can’t say for sure. Maybe it doesn’t matter. I’m just grateful to be surrounded by so many wonderful people.

For the next few days, Tani would be walking with us through part of Miyazaki. We were in for a great time.

Native Trail

Kyushu Nature Trail’s designation is as a “long-distance nature trail”. But the Miyazaki portion is mostly paved roads, and what wasn’t paved was overgrown –– tall grass, fallen trees –– and poorly maintained.

“Are we really on the right path?” Hitoshi asked.

“According to the GPS, we are exactly on it.”

“There seems to be something that looks like a trail over there!”

“No. That looks more like an animal path.”

This was a conversation that repeated itself whenever we left paved roads and entered a trail.

The Miyazaki portion seems to attract few hikers. Which is understandable, given how much of it is paved and how it traverses only two peaks –– Mt. Sobo and Mt. Takachiho.

Using our GPS, we bushwhacked through the undergrowth and hurdled fallen trees, before running into a net used to keep deer out.

“Hey! There’s a net here!”

“But the route continues beyond it.”

“You’re right.”

“What should we do?”

“Let’s try walking along the net for now.”

After a few minutes, our GPS revealed that we were nowhere near the trail. Clearly, we needed to go through the net. We found a hole torn by animals, ducked through it, and ended up on a game trail. The ground was covered in dead leaves, and an unidentifiable animal smell filled our nostrils.

“We’re almost at the forest road!”

“We should be able to connect back to the trail that way.”

We emerged from the trees but the road was a three or four-meter drop below us. We found a spot to safely descend and carefully made our way down.

There’s a vicious cycle at work here. If hardly anyone walks a trail, there’s no need to maintain it. If it’s not maintained, it soon becomes overgrown and impassable. Even if a trail that’s fallen into disuse occasionally attracts hikers, they probably wouldn’t be eager to revisit it. Allocating funds for proper maintenance is the only way to prevent Japan’s long-distance nature trails from disappearing.

On a tough trail, a paved road can actually bring relief. It’s not unlike dipping into the cooling waters of an outdoor pool after a sauna.

That day was another grueling slog along an overgrown trail. We had planned to walk 18 km. Assuming we covered 4 km per hour, we’d make it in about 4.5 hours. We were so relaxed at the campsite in the morning that it was after 09:00 when we set off. By the afternoon, we had only gone half the distance.

As we crested the final pass, we walked only a short section of trail. Our GPS guided us up a paved road that had no cars. Which made us wonder: Why had this road been built?

“Masaru, it looks like we go this way.” Hitoshi pointed to the slope next to the road, with tall grass and trees.

“There’s no way. This can’t be right!”

“Look at the GPS.”

“Could the GPS be wrong?”

“I hope it is.”

We walked further on the road to look for signs of a trail, but found none. We decided to take a break and put down our packs. Had there really been people walking this trail? Locals told us there had been busloads of hikers in the early days after the Kyushu Nature Trails opened in 1980. It was hard to imagine that now.

We looked at where the trail was supposed to be. Neither of us was eager to push through.

“Shall we get going?”

“Why am I always the one going first?” I shouted over my shoulder at Hitoshi.

“Because you’re stronger!”

“You should take the lead sometimes!”

“I need to take photos!”

I’d forgotten about that and the fact that Hitoshi’s load was noticeably heavier than mine. But bushwhacking was hard work. I had to watch out for loose rocks underfoot that might trip me up. And spider webs: I’d lost count of the number of times I’d walked straight into a massive sticky web blocking the path.

There was no discernable path. Occasionally, we came across remnants of steps partially buried on the mountainside. There were collapsed sections of loose rock that hinted at a trail. I imagined inadvertently triggering a rockslide that tumbled toward Hitoshi behind me, and concentrated on my every step. I couldn’t remember being this nervous on a trail since climbing the snowy sections of the Sierra Nevada range in California.

On the steep slope, I noticed a signpost for the Kyushu Nature Trail. Seeing it stirred something within me. How long had it been standing here? Forty, maybe fifty years? What had happened here over the decades?

Even after we’d left the signpost behind, it stuck in my head.

We crossed over the pass and arrived near the source of the Ishanami River. There was nobody around. It was tranquil, beautiful. Exhausted, we set down our packs and rested.

I took off my shoes, dipped my feet in the river, and watched the water flow by. It reminded me of being at Iwase River, near Mt. Okue and Mt. Sobo, in the summer. Shu, the owner of Cafe&Bar Tent, in Moji Port, and I had gone there to fish and hike. Back then, Shu had talked about the difference between wild and native fish in streams. “Fish that have adapted after being raised and released are considered ‘wild,’ as opposed to the ‘native’ fish that have always lived there. Even if they are the same species, the shapes of their fins can differ. .

For some reason, that memory made me think of the trail signpost we’d passed. Would a signpost be wild or native? Someone had to make it and place it there, so wild seemed the more accurate description. Yet it had probably been there so long that native felt suitable.

The section of the trail that we were walking was not easy. We’d bushwhacked and navigated fallen trees, loose rocks and spider webs. I can’t think of many people who would consider that an enticing hike. I’d prefer to be on a trail that’s nice enough to run on. Then again, I wouldn’t call nature trails boring.

I had a new idea: calling long-distance nature trails “native trails”.

Created a half century ago, the Kyushu Nature Trail might be the official route, but its state of disrepair made me wonder whether a different path would’ve been better. Easier, certainly. But think of it in a different light –– as a native trail, one that’s been there for so long and is imbued with the history and wisdom of hikers and trailblazers in its past –– and the journey changes. It’s no longer a godforsaken route where you’re forced to bushwhack, trip over loose rocks and vault over fallen trees. It has a romantic backstory, and you’re an adventurer.

I adjusted my pack and resumed my walk through the bushes. The scenery was as desolate as before. Nothing hadn’t changed around me but everything looked different.

Wild Hiker

We had one day left on our 350-km journey. By then, we had been on the trail for more than weeks. The daytime heat had become more bearable. It was still warm enough to make us sweat, but night brought a perfect coolness as we slept.

The day before, we’d spotted Mt. Takachiho, our final destination, in the distance. The peak straddles Miyazaki and Kagoshima prefectures.

“Tomorrow it ends.”

“It felt like it went by in a flash.”

“What day is it today?”

“Day 16!”

Amid our usual banter, we noticed another hiker approaching.

His clothes were soaked through and faded, and his Pa’lante backpack was so worn that it bore no resemblance to mine. His skin was tanned, and he wore a thick beard.

“Masaru!”

“Oh! Sagara!”

“Long time, no see!”

“Good to see you!”

Sagara is from Kagoshima prefecture. He had hiked the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) in 2023 and had just returned to Japan from the US the day before. We had been in contact and had planned to meet up near the end of Miyazaki trail. I had adjusted my schedule to await his return. He was fresh off the plane and looked every bit the wild hiker.

“I thought you might have finished walking already! You walk fast!” Sagara said.

“Walking 40 to 50 km a day, we would only spend just over 10 days covering 350 km.”

“True. I’m glad I made it in time!”

“How was the PCT?” I asked.

I knew there was no way for him to adequately summarize his long walk. He probably hadn’t fully digested everything that he’d experienced. But I had to ask.

“It was amazing!” he replied.

“Are you already thinking about doing it again somewhere else?”

“I don’t know yet. To walk that kind of distance again, I’d need some negative energy to drive me.”

“What do you mean by that?” I asked.

“You can’t walk that far just for fun.”

I think I understood what he was saying. Walking as far and for as long as Sagara did, there were likely few moments of joy. Mostly, he would have experienced hardship. Long-distance hikers have all been there. And yet, by the end, we’re smiling, declaring it the best experience. This is the magic of long trails.

We arrived at our final campsite, Okukirishima Oujibaru Park. It was a weekday. The only others there were a couple with a large tent enjoying their BBQ. We checked in and pitched our tents away from theirs so as not to disturb them.

We took a bath at a nearby hot spring and then commenced our evening festivities.

The sun had set behind Mt. Takachiho and the temperature had fallen. We set out our ground sheets and each started preparing a simple meal by the light from our headlamps. It was our final night, but we were still eating like hikers. The only difference was that we would down plenty of beers and doze off on a soft mattress of grass.

Sagara asked: “Did you see anyone else hiking the Miyazaki trail?”

“Not a soul. The only places we saw people were at Mt. Sobo and Takachiho Gorge.”

“That’s what I figured.”

“Have you ever hiked the Kyushu Nature Trail in Kagoshima?” I asked him.

“Before going to the US to hike the PCT, I often walked the Kagoshima section. There’s hardly anyone on it,” said Sagara. The Kagoshima trail had been his dry run for the PCT.

We were talking about Japan but being there with Hitoshi and Sagara and the sky full of stars reminded me of hiking the US long trails. That was on my mind as I lay down in my sleeping bag. A full moon loomed above us.

“I’m too lazy to get into my tent,” someone said. There wasn’t much dew on the grass. We all bedded down under the open sky. It didn’t take us long to drift off. Why had we even bothered to set up tents? I credit the wild hiker fresh from his US journey for that night of rejuvenating, tentless sleep.

HIKE MIYAZAKI

Seventeen days. I couldn’t tell whether that was long or short. On our last day, we reached the Kirishima Higashi Shrine trailhead for Mt. Takachiho. It was late October but the weather was still mild enough for a thin shirt and shorts. It felt like we had been chasing the remnants of summer.

I’m still a stranger to most of Japan’s long-distance nature trails. But I see their potential. Here’s why: They’re the gateway to a journey.

Walking long trails differs from mountaineering in one important way: on long trails, you embrace the unexpected; when mountaineering, you do what you can to avoid it. With mountaineering, you’re traveling at higher altitudes, going to uninhabited, sometimes inhospitable places. You rely on your gear and your wits, you plan meticulously, and you try to minimize the unexpected by sticking to your plans. A slip-up could cost you your life.

Long-trail walking is lower stakes. You’re crossing in and out of the civilized and natural worlds, so help is never too far away. On these walks, the unexpected –– encounters with locals, a disappearing trail –– can add a colorful dimension to the journey.

At the summit of Mt. Takachiho, having just been through a thunderstorm, I watched the winds chase after the receding rain clouds. The end of the Miyazaki portion of the trail coincided with what felt like the end of summer. As we shivered in our clothes and descended the mountain’s western slope, we saw Kagoshima city and the island of Sakurajima, marked by its smoke-billowing volcano.

I want to thank Hitoshi, my walking companion; Sagara, who joined us so soon after returning from his PCT hike; Daisuke and Tani, who delivered trail magic; and the many others whom we encountered along the way. It wasn’t an easy or well-worn path but it brought plenty of rewards.

There’s no particular reason our walk had to be in Miyazaki, though. There are so many others we could have chosen from, around major metropolitan areas, farflung towns and places where only locals recognize the mountains. At the end of our Hike Miyazaki journey, we came across a signpost near Kirishima Shrine that marked the beginning of another journey for another time: “Kyushu Nature Trail, Kagoshima Prefecture”.

I’m convinced that more people will walk Japan’s long-distance nature trails in the future. That time is probably not far off. These trails connecting the rural and urban, the inhabited and uninhabited might offer an alternative to the more common practice of hiking up mountains. As awareness of nature trails spreads, the overgrown paths -– and the bushwhacking needed to follow them –– will become a thing of the past. When that happens, the overgrown trails -– and the bushwhacking needed to follow them –– will become a thing of the past. Fewer people will experience what I felt: the joy of the slog along these forgotten routes. But I don’t think long-distance nature trails are on the verge of disappearing. Not at all. My own trip showed me how much –– and potential –– they future holds plenty of potential in their future.

【END】

Masaru Kiyota is the owner of cafe & bar peg., in Osaka, and frequently shares his travel experiences through social media and podcasts. In 2013, he cycled around Japan. A year later, he spent a working holiday in Australia. From 2015 to 2016, Masaru traveled around the world. In 2017, he hiked the Pacific Crest Trail in the US, followed by the Appalachian Trail in 2018 and the Continental Divide Trail in 2019. He walked the Michinoku Coastal Trail in Japan’s northeastern Tohoku region in 2020.