Understanding the History of Ultralight Hiking Through Backpacks

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

Understanding the History of Ultralight Hiking Through Backpacks

Text: Seimi Rin

Photos: Masaaki Mita

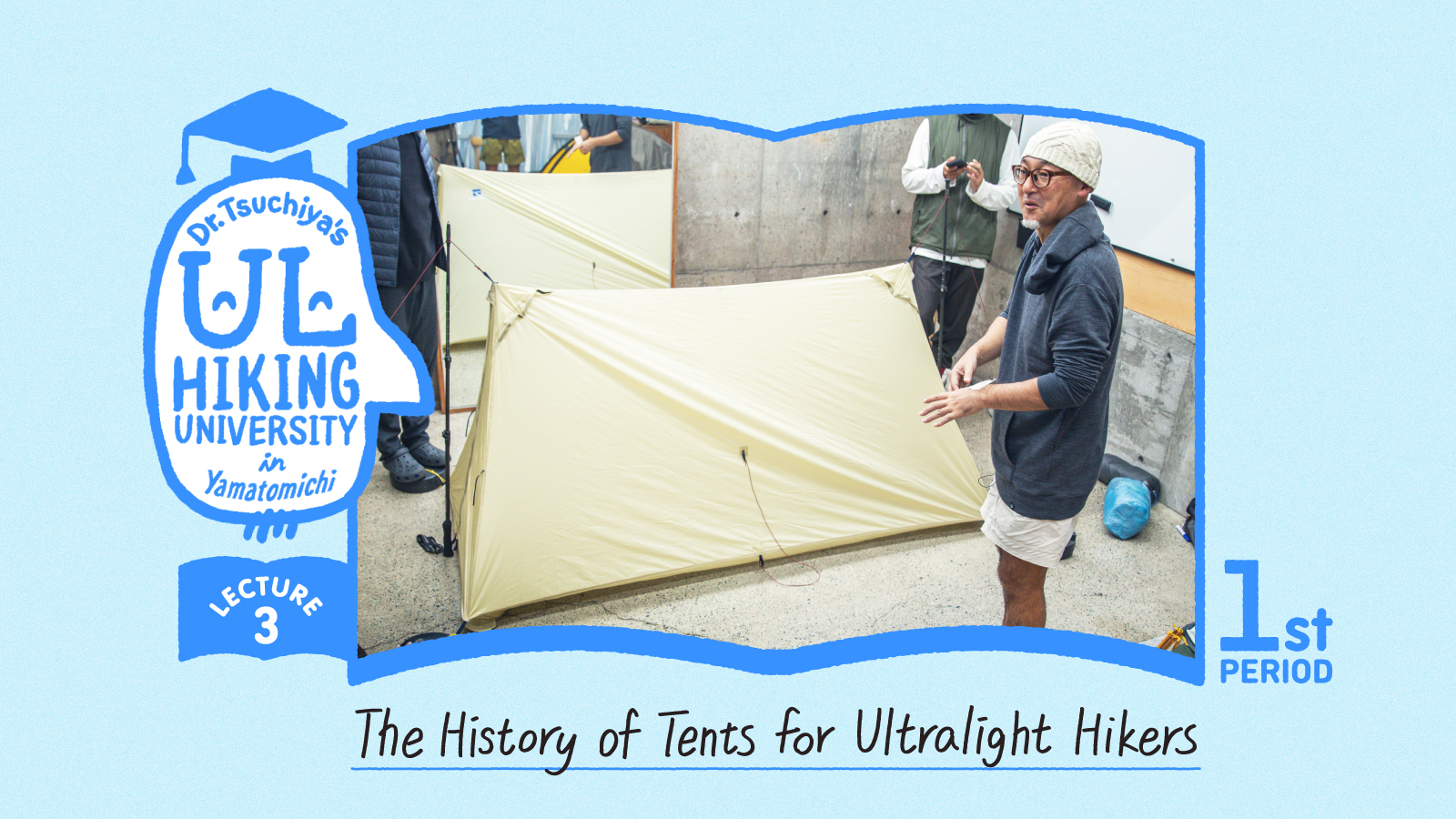

Tomoyoshi Tsuchiya, owner of Hiker’s Depot in Tokyo and one of Japan’s ultralight hiking pioneers, is the author of Ultralight Hiking (2011) and a frequent Yamatomichi collaborator. Every few months, Tsuchiya will host a lecture at Yamatomichi’s Laboratory, in Kamakura, covering the history of ultralight hiking and the evolution of its practitioners’ gear, from packs and tents to shoes and sleeping bags. His first lecture explores the birth of ultralight hiking backpacks.

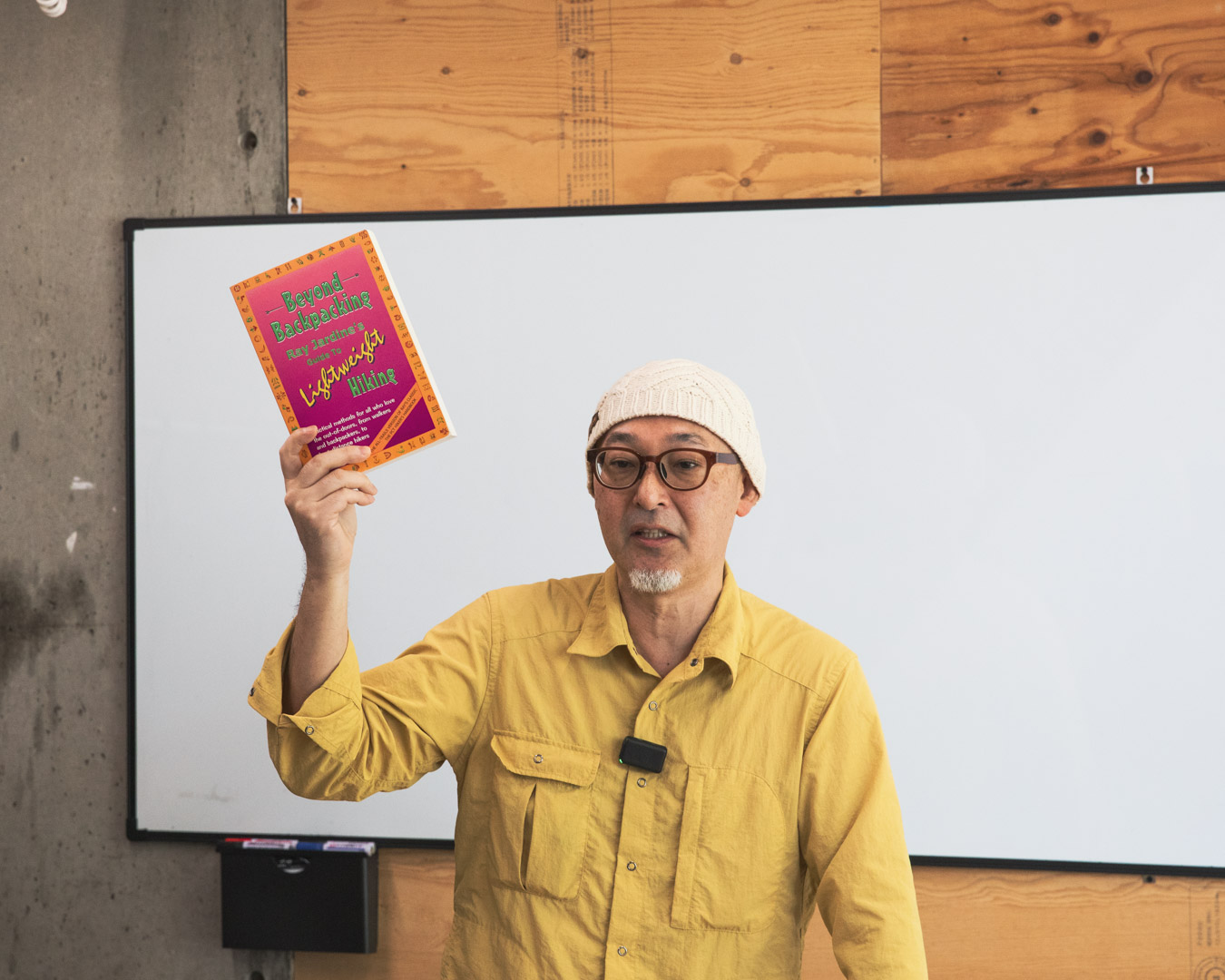

Tomoyoshi Tsuchiya speaks with Yamatomichi staff at the Yamatomichi Laboratory In Kamakura, Kanagawa prefecture

Introduction

My name is Tomoyoshi Tsuchiya. I run a shop called Hiker’s Depot in Mitaka, Tokyo. Two years ago, Yamatomichi co-founder Akira Natsume and I began discussing the possibility of a collaboration. Today’s lecture is the result of those discussions.

At Yamatomichi, everyone is incredibly knowledgeable about the brand’s products. But you might not always grasp the shifts taking place in the industry. Understanding where Yamatomichi’s backpacks fit in the broader market context can strengthen the brand and help you meet customers’ needs.

Today, I will talk about how long-distance hiking spawned ultralight hiking and changed backpack designs. I’ll define ultralight backpacks that have no frame or hip belt as well as backpacks that come with these features.

Tsuchiya introduced the culture and methodology of ultralight hiking in Japan

The Foundation of Ultralight Backpacking

Ray Jardine’s PCT Hiker’s Handbook (1991) and his revised versions Beyond Backpacking (1998) and Trail Life are often considered the origin of ultralight hiking and his “Ray-Way” methodology.

Tsuchiya talks about Beyond Backpacking: Ray Jardine’s Guide to Lightweight Hiking (1999)

Ray-Way emerged as a response to the traditional concept of backpacking. In 1968, Colin Fletcher wrote The Complete Walker, a seminal work on backpacking in the US. It had a significant influence on American outdoor culture in the 1970s and reached Japan in the 1980s through Outdoor and other magazines as well as books by writers like Yasuhiko Kobayashi*.

*Born in 1935. Painter and illustrator. In the 1970s and 1980s, Kobayashi wrote The Heavy Duty Book, The Era of Illustrated Reports and One Hundred Low Mountains in Japan, which helped spread US outdoor culture in Japan.

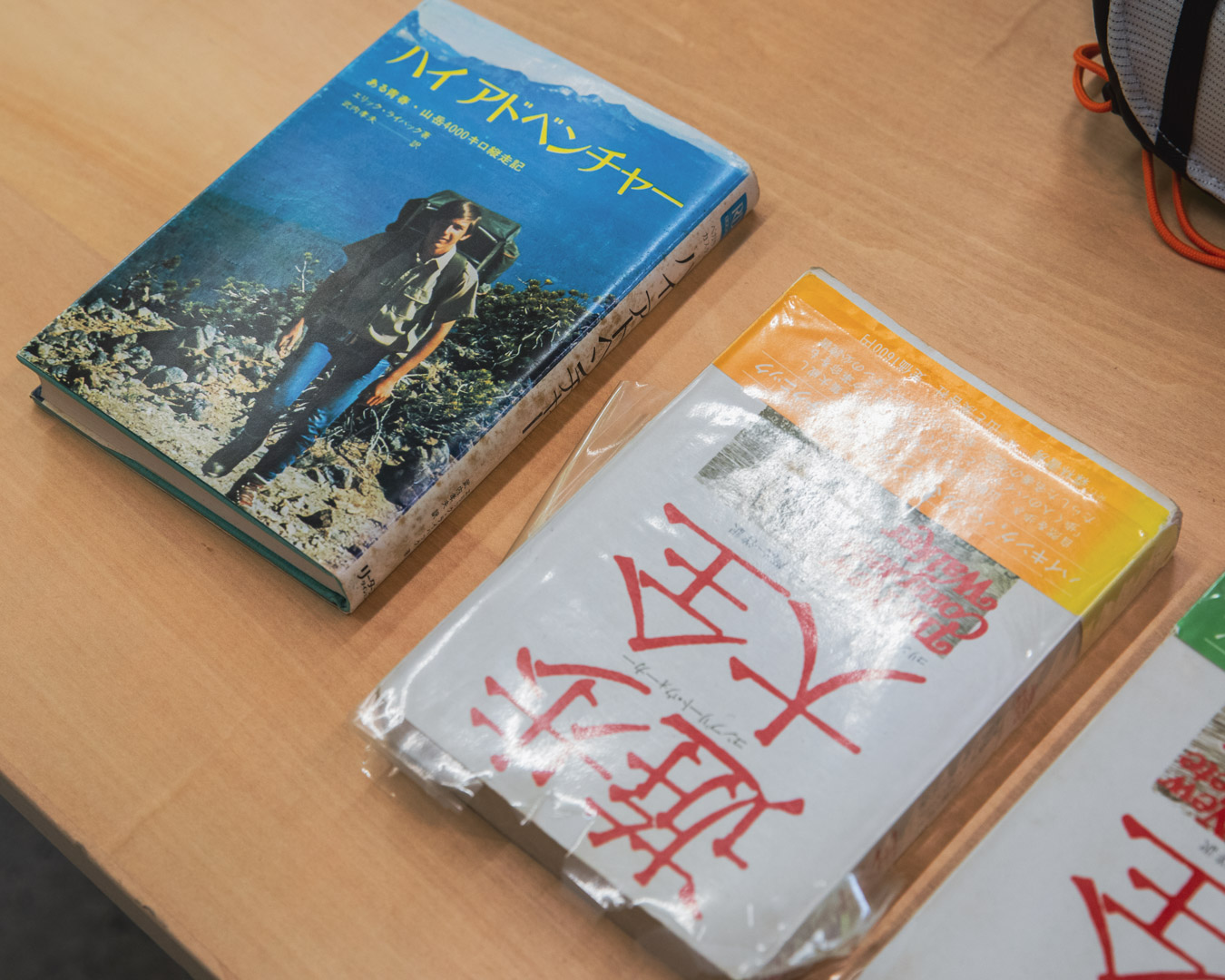

Tsuchiya’s copies of “The High Adventure of Eric Ryback” and “The Complete Walker.”

In 1971, 19-year-old Eric Ryback completed the entire 4,265-km Pacific Crest Trail* (PCT) –– along the West coast of the US, north to south, from the Canadian border to the Mexican border –– in a single season. His book, The High Adventure of Eric Ryback (1971), featured a cover photo of him carrying a traditional pack with an external frame.

*The Pacific Crest Trail is one of the three great long-distance hiking trails in the US, along with the Appalachian Trail (AT) and Continental Divide Trail (CDT). Over the years, Ryback’s accomplishment has been disputed by claims that he hitchhiked, circumventing parts of the PCT.

In The Complete Walker, Colin Fletcher emphasized the twin concepts of walking and living. Backpacking in those days involved carrying nearly everything from home. Packs were large and heavy, sometimes weighing around 30 kg. This was how you survived in the wilderness in the 1970s and 1980s. Few people were hiking the PCT, and among those who tried, only 5% completed the trail. The trails weren’t well-maintained or fully connected, and it was only natural for thru-hikers to lug around a lot of gear.

Long Distance Trails and Ultralight Hiking

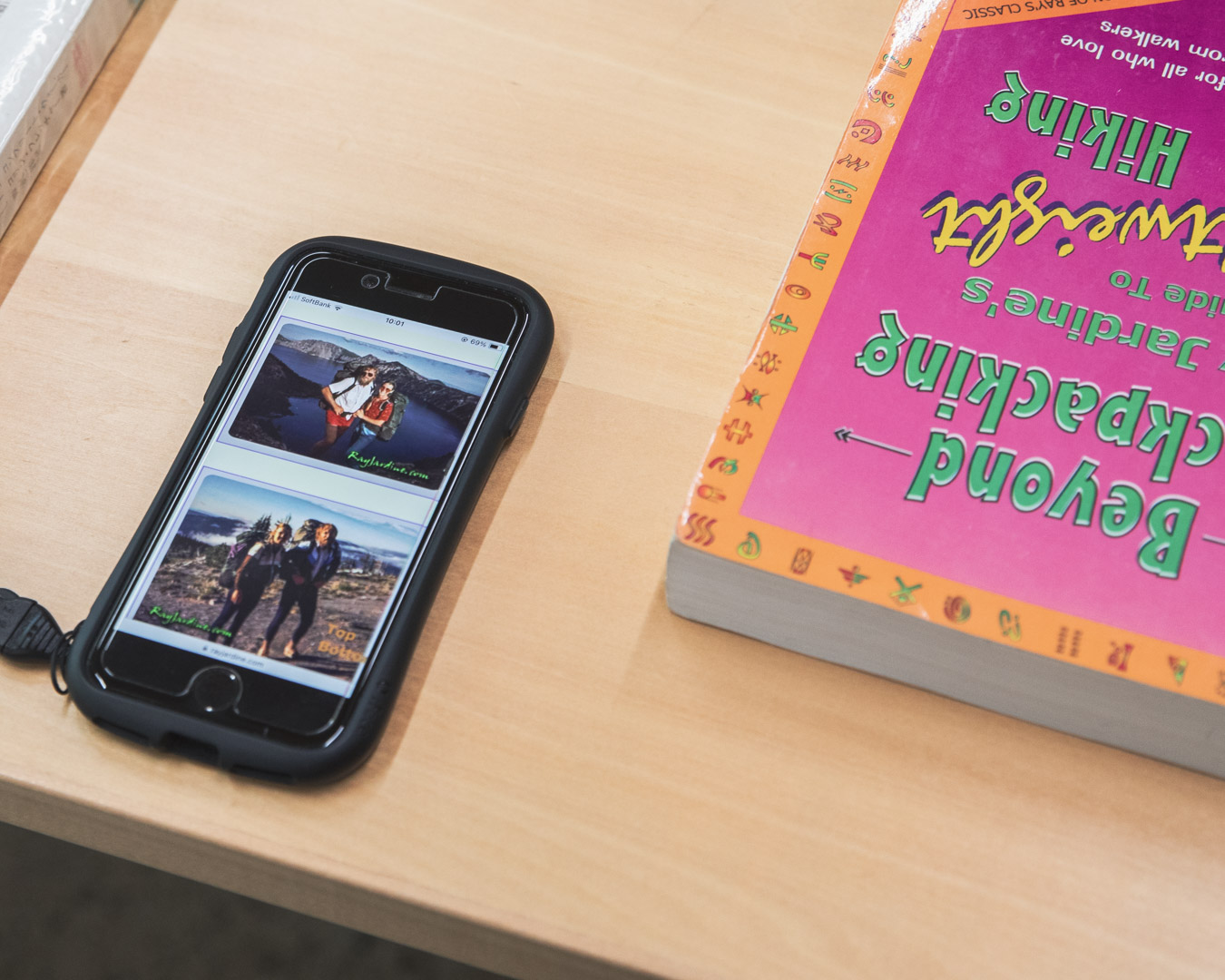

In 1987, Colorado native Ray Jardine completed his first thru-hike of the PCT while carrying quite a large pack. A few years later, Ray returned to the trail, accompanied by his wife Jenny. Their numerous challenges and injuries on the trip led Ray to question the need for a 30-kg pack on a 4,000-km journey. He thought the heavy load might be to blame for the low success rate of thru-hikers tackling long-distance trails.

Ray Jardine’s website features photos of his early backpacking days

Other hikers were experiencing problems similar to Ray’s. In 1994, Norio Kato* –– who championed long-trail hiking and US national parks in Japan –– trekked the 340-km John Muir Trail (JMT) shouldering 45 kg. By the time he reached Tuolumne Meadows, on the eastern side of Yosemite National Park, he was forced to quit. A year later, Kato headed back to hike the JMT, but with a less burdensome 30-kg pack. It’s worth noting that, with the ultralight gear that’s available today, you could cover the 36 km from the Happy Isles trailhead to Tuolumne Meadows in a day.

*Born in 1949 (died 2013). A writer and pioneering researcher who introduced John Muir and US long-distance trail hiking to Japan, Kato contributed to opening the 110-km Shin-etsu Trail, along the border between Nagano and Niigata prefectures. His books in Japanese include The Saint of the Forest: The Father of Nature Conservation John Muir (1995), Walking the John Muir Trail (1999), and Heading for the Maine Woods (2011).

Ray’s radical ideas to lightweight hiking grew out of his suspicions about the link between heavy packs and injuries on the trail. His experimentation with less burdensome gear was also influenced by what he viewed as commercialism in the outdoor products sector. He compiled his practical approach to long-distance hiking –– dubbed Ray-Way –– in his book, PCT Hiker’s Handbook (1992). Ray-Way is widely credited with the mainstream spread of ultralight hiking.

Ray Jardine’s portrait taken on the PCT from Trail Life (1996) –– bare-chested, wearing spandex shorts and toting a lightweight pack –– remains an iconic symbol of the Ray-Way movement

Ray’s emphasis was on walking, and he simplified every aspect of being on the trail to the bare essentials. He slept under a tarp instead of in a tent. He cooked on an alcohol stove instead of a gasoline stove. Since he was traveling with his wife, he reasoned that a single, shared, lower-grade sleeping bag, used as a blanket to maintain their body heat, would suffice. These decisions reduced the weight of their gear without sacrificing on comfort.

Jenny, Ray’s wife, with their Ray-Way homemade backpacks and tarp in Trail Life

Ray and Jenny’s unconventional ideas challenged traditions and focused on walking comfort without major compromises on other aspects of trail life. This is key to understanding the rationale for tarps and other ultralight camping equipment and the overall ultralight hiking philosophy.

The GoLite Breeze

Ray-Way backpack successor

To promote Ray-Way as a long-distance hiking methodology, Ray sold DIY kits for the backpacks, tarps and sleeping quilts that he designed. Some of you might have made a backpack using these kits. In 1998, Ray’s backpack design was commercialized by Boulder, Colorado-based outdoor equipment and clothing brand GoLite*.

*GoLite, a pioneering ultralight brand founded by Kim and Demetri Coupounas in 1998, sold the Breeze backpack as its first product. In 2014, the company filed for bankruptcy. Four years later, under new management, GoLite relaunched as an outdoor apparel brand, and since then has re-released products like the Jam and Shangri-La backpacks and tents.

The GoLite Breeze should feel very familiar to everyone at Yamatomichi. The front and side pockets are mesh. The pack has shoulder straps but no lid, frame, padding or hip belt. While Yamatomichi’s MINI and MINI2 backpacks have some padding and a hip belt, the basic structure is the same as the GoLite. This style is the starting point for the diverse range of ultralight backpacks sold today.

The GoLite Breeze, released in 1998, has all the features typical of today’s ultralight backpacks

The GoLite Breeze has no frame, padding, hip belt or sternum strap.

Ultralight hikers carrying only what’s essential can reduce their base weight –– the weight of gear, excluding food, water and fuel –– to less than 4.5 kg. Even with food and water, it’s possible to carry less than 10 kg. This allows hikers to focus on walking, significantly lowering the risk of injury and increasing the likelihood that they will complete a thru-hike. It’s exactly what Ray’s improvements were designed to achieve.

In the 2000s, Ryan Jordan’s Backpacking Light website gained a following. Early on, the online discussions focused on applying Ray-Way to hikes and trail outings over weekends or several days, not just long-distance hiking. As enthusiasts pushed the idea to its lightweight extremes, it fueled competition for brands to produce gear that weighed even less. The term “ultralight” emerged during these discussions and became a kind of collective intelligence created by and for hikers.

This term “ultralight” had a big impact on me. It was a different approach to reducing weight, with even more emphasis on connecting with nature as well as thinking logically about base weight. I felt a strong attachment to and was fascinated by the cultural side of this approach.

The Gossamer Gear Murmur’s impact on ultralight hiking

Around the time Ryan’s Backpacking Light site was winning converts, one backpack had become a symbol of ultralight hiking in Japan: the Gossamer Gear Murmur. Gossamer Gear was founded in 1998 by Glen Van Peski, who got his start by sewing backpacks for his children at home in Carlsbad, California. Eventually, he sold his packs to hikers and even shared his patterns.

Gossamer Gear was known for its extremely lightweight, small-capacity backpacks, notably its G5 models. They were specifically designed for three or four-day hiking trips. The Murmurhad a hip belt, but its fabric was thinner than the GoLite Breeze’s. The Murmur came under fire and was criticized by traditional hikers, who mocked the pack as “extreme lightweighting” and questioned its utility in the mountains.

In the early 2000s, I was working at an outdoor gear shop. I thought: “I’ll hike with this kind of gear.” I was eager to prove a point to our hiking community in Japan. But I also experienced setbacks along the way.

Gossamer Gear’s founder Glen Van Peski carried this Murmur backpack while hiking in Japan in 2010

The Murmur has no frame and features a pocket for a sleeping pad to be inserted as a back pad

This radical shift in design and appearance captivated numerous hikers. The ultralight methodology gradually gained a following around the mid to late 2000s as people realized that it could also be applied to casual hiking,